-

Essay #15 – Memorials for Murdered Family

After returning from Germany in June, 2022, my father suggested that I turn my attention to having memorials placed for those who were murdered by the Nazis. Now in January 2023, I sit at my desk in New York City with a new mission.

At my desk at our New York City apartment To determine who in my family perished, I took a detailed look at my family tree, which now has 590 names. Since the German government decided that a memorial should be at the last residence that was “freely chosen” by a Jewish person, I need an exact address to give to the appropriate town or city. As part of my research, I have found family members previously unknown to me who share an interest in our history. This journey brings together a family that was scattered around the globe and seeks to understand what the hell happened, if any genocide can ever be understood.

In many ways we are among the more fortunate. Many in my family managed to get out of Germany before it was too late. Though such escapes gave the German Jews a greater survival rate than countries like Poland with many more Jews (more on that in another post), all of my relatives who did not leave Germany before WW2 began were murdered. Of those who fled, only one Freund relative, who had moved from Germany to Holland before the war, survived deportation to a concentration camp.

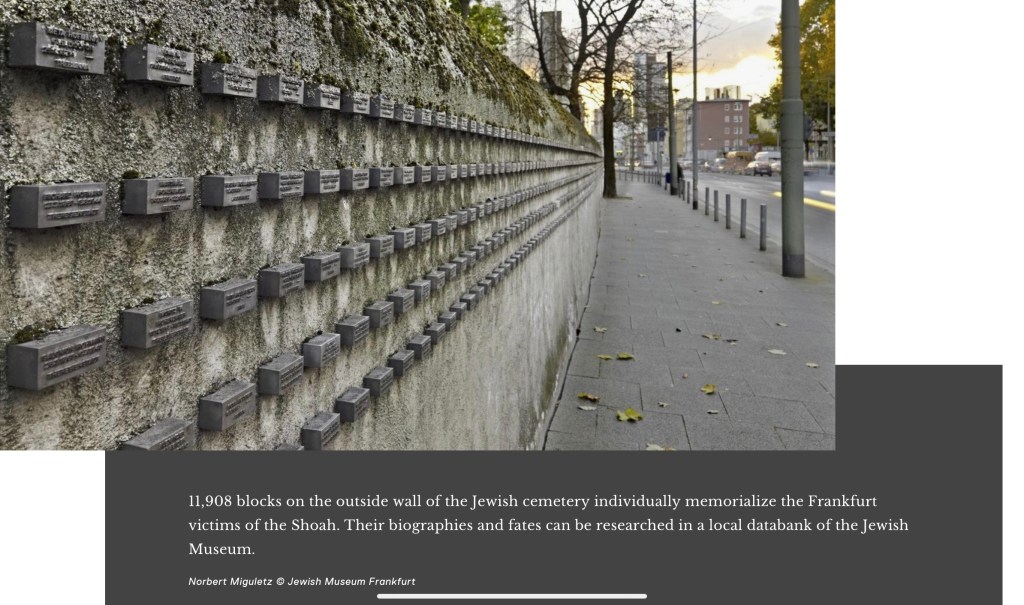

The victims of the Nazi regime are remembered in Germany and elsewhere with many types of memorials. In some cities, like Nürnberg, Alsfeld and Aschaffenburg, Stolpersteine or stumbling stones (brass plates) are set into the street in front of the house where the Jewish person lived. In Frankfurt, there are steel blocks with the names of nearly 12,000 Jews in one place! In Munich, memorials are placed on the side of buildings and columns outside the houses. In Fulda there are real stones outside the synagogue.

This is personal. Members of family either already have a memorial or will have a memorial in each of these cities mentioned in the coming years. I have been working with the cities of Nürnberg and Munich to remember my Freund family in May 2023 and in 2024. I plan to see all the memorials that are in place, most of which I have not visited because I did not know about them.

In my mother’s hometown of Alsfeld, Germany, are Stolpersteine for her Uncle Markus and Aunt Therese. “Deported 1941. Murdered in Łódź.” I never met my mother’s Aunt Therese Strauss née Steinberger or her husband Markus Strauss. They lived around the corner from my mom in Alsfeld. While my grandfather Adolf Steinberger moved to Haifa with his family in 1933 (my mother was just 13), Aunt Theresa stayed too long, trusting in Germany, declining opportunities to go to Cuba and South Africa.

Therese and Markus moved to Frankfurt in 1939 as Jews in small towns like Alsfeld felt the Jew-hatred. In a big city they could be more anonymous. No matter. They were deported to the ghetto in Łódź, then Poland’s second largest city, in October 1941.

Before the war, the city of Łódź had 230,000 Jews. Jews were 31% of the city’s population. By comparison, Germany as a whole had 500,000 Jews in 1933; nearly two thirds of them had fled by the time the war began in 1939. My great aunt and great uncle and Jewish deportees from elsewhere were forced into the Łódź ghetto. It had no water or electricity. The average person was allocated about 1,000 calories per day. Death came from starvation, disease, exposure, shooting, and forced labor. Therese and Markus perished there. Their sons, pictured below, got out of Germany before the war, one to South Africa and one to England.

Here is my immediate Steinberger family in Alsfeld, with Therese and Markus at top right. My mother is the seated at bottom left, along with two male Strauss cousins and sister Charlotte. My maternal grandparents are on the top left and my great grandmother is in the middle. The City of Frankfurt has erected a wall bearing steel blocks with the names of nearly 12,000 Jews, including my great aunt Therese and great uncle Markus and other Freund family members. My husband and I will visit in May. It is hard to imagine just how long is this concrete memorial.

In Frankfurt, the city erected steel blocks with the names of nearly 12,000 Jews, including my great aunt Therese and great uncle Markus. Irene Freund, I wish I could have met you. In other circumstances, we would have met at family events because your father and my grandfather (cousins) were born in the small town of Kleinwallstadt, with a population of 5,700 today.

You were an independent, unmarried woman who had a career! You worked in Aschaffenburg as an office assistant and private secretary.

You were born on June 21, 1900 in Aschaffenburg, Germany. Your father, Lippmann Freund, worked as a fruit dealer who married Fanny, née Koschland.

On April 23, 1942, you were taken to Würzburg. Two days later, you were deported to Krasniczyn, Poland. You were murdered there or in another camp in the Lublin area in the same year. A stumbling block in Aschaffenburg commemorates you. You were just 42 years old.

Stolperstein for Irene Freund in Aschaffenburg, Germany. You may know that the Germans long have kept detailed records of birth, death and every change of residence. But Nazi era records aren’t always easily available today. Not everything has been digitized. And sometimes local officials want to keep skeletons in the closet.

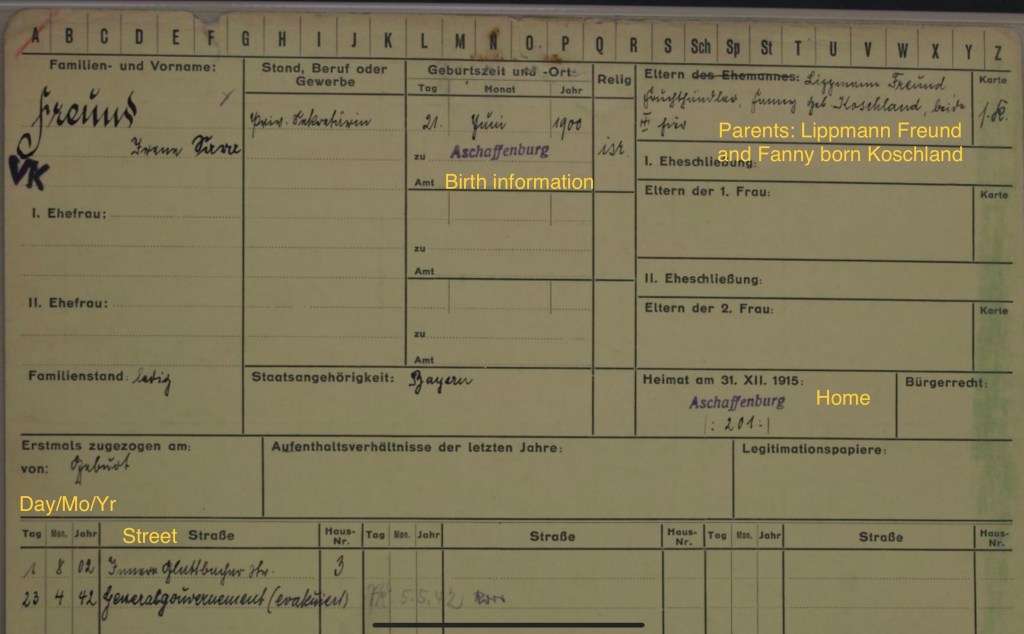

In the last six years, I have been studying German, which has helped me read the old documents that are scattered across the Internet. Below is an example from the City of Aschaffenburg with Irene Freund’s details.

The card above shows Irene Freund’s home in Aschaffenburg, her birth information and her parents names. I added the English translations.

This document records Irene’s birth and her parents. In future posts, I will write about Freund family members who are just getting to know each other. I also will explain how I am working with officials in Munich and Nürnberg and will be speaking to students in Fulda, Kleinwallstadt and maybe other towns, on my upcoming trip.

In the meantime, you can read about Stolpersteine and watch a video about them here.

-

Day #14 – My Roots Tour’s End

I’m home and thinking about our trip to Germany.

Many smart, kind, generous people made this trip possible and special.

Already, I miss the coffee and my new friends.

German coffee: strong and good. I’d order a cup for Jeffrey and drink his too. On prior trips to Germany, I couldn’t sleep. I feared that Hitler would jump out of the closet in my hotel room or that I would be arrested on the street. In those days, former German Nazis were alive and well.

Today, the youngest Hitler voter would be 110 years old. A Nazi soldier aged 18 in 1945 would be 95 now. My fear of the old Nazis is gone.

Many thoughts whirl in my head. This trip involved visits to my family’s hometowns and to historic sites, and talking about the present and the past with today’s Germans. This was not a cemetery tour. We did not say Kaddish for people I never knew or met. “Been there, done that.”

This tour engaged me with Germans born after WWII. We put aside who was responsible for the war. None of us in the post-war generation was responsible for anything.

Like me, these Germans were raised by parents who had suffered. My parents’ trauma came from being frightened and uprooted, from being strangers in strange lands. The Germans’ parents were scarred by invasions, bombing, hunger, years of military service, years in prison camps; some screamed in their sleep.

Our parents’ traumas great and small influenced our childhood development. We shared stories and the effects the war era had on us, the second generation. We lived with parents who acted out their pain, or refused to talk about their experiences, or searched for their lost childhoods. Sometimes this made us anxious and scared. Sometimes we pass our anxieties on to our own children.

My German contemporaries and I became friends. Our friendship has eased my mind. Our exchanges were meaningful and cathartic for all of us. My hope is that we can heal some of one another’s pain.

As I traveled from place to place, I couldn’t escape the fact that the Jewish people rooted in Germany for centuries, have vanished. Larger cities have a few Jews and synagogues, but most of those Jews are from the former Soviet bloc. There are a few Israeli transplants. The Jews who spoke and ate and joked and kept house and lived like my parents and their parents, are gone. They left Germany or were murdered.

It makes sense that the German Jews made new lives elsewhere for themselves and their descendants. But many Germans today miss the diversity that my family and others brought. Some of my new friends told me that they’re sad that people like us don’t live in town. They said that with Jewish neighbors, their communities would be more vibrant and interesting. We would have been friends.

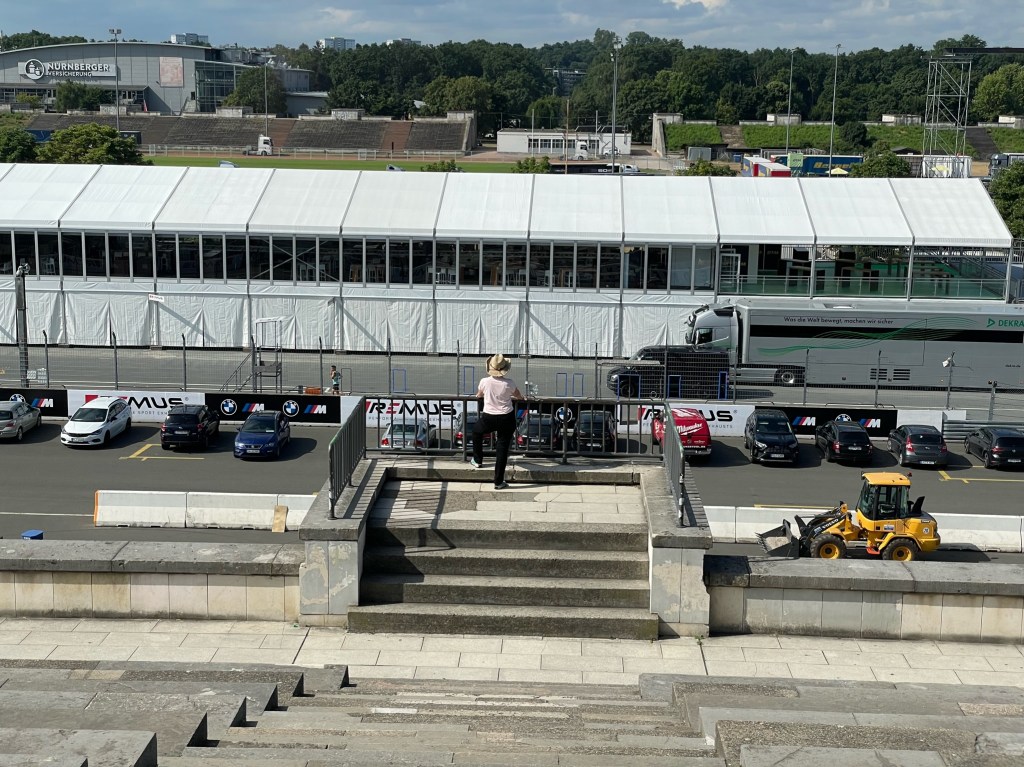

Yet although most of Germany is as Hitler wished—Judenrein, free of Jews—my people triumphed in the end. My grandparents’ Jewish granddaughter stood atop the annihilated dictator’s Nuremberg platform. I towered over him!

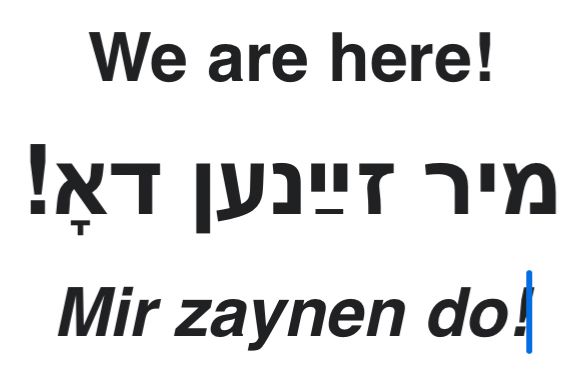

As my husband says in Yiddish, the language of his grandparents, mir zaynen do.

Hirsh Glick (1922-1944) wrote the Yiddish Zog Nit Kaynmol (“Never Say”) or Partisaner Lid (“Partisan Song”), from which these words are taken, in the Vilna (Lithuania) Ghetto in 1943. Partisans spoke Yiddish, not German. Click here and scroll down to listen to a former partisan sing the song in 1946. I thank everyone who made my trip so meaningful. There are too many to name. A few of the many who stand out:

Markus and Katrin included us in the wedding celebration of Lily (and Ross).

Siblings Moran (next to me) and Itamar (in hat), with whom I share Israel roots, welcomed us to Munich.

When Christian heard that my dad rode a Nuremberg tram to school, he broke museum rules, unlocked the tram and showed us around inside!

The women at a Nuremberg Lebkuchen store made me welcome and helped with my selection. They enjoyed hearing my family’s Lebkuchen story.

My Aschaffenburg friend Iris spent three days with us, organized tours, shared her stories and opened her home. Iris has helped me enormously with family research.

Achim took me around Kleinwallstadt and shared old documents from my forebears. He invited my father to share his memories with German students online.

Gerd in Reichelsheim showed me around and gave me a ton of information on the Joseph family. Louis Joseph, my cousin who in 1893 emigrated to the U.S. from Reichelsheim, made possible my father’s 1937 escape.

These new friends took us around Miltenberg and bought us dessert at Cafe Sel, where my parents went for treats when they were children.

Marga and her family continued my Alsfeld connection established by Marga’s late husband, Heinz. They helped me translate old handwritten letters.

Monika and her friends enriched our time in Alsfeld, where my mother was born and raised.

Daniela and Carolina spent a whole day giving us an inside look at the remnants of Jewish life in Alsfeld and their educational project, [click here] Speier House, in the neighboring town of Angenrod.

Aegedus (left) and Joachim (center) joined us for dinner as we talked about our lives and formed new friendships.

Melina saw two strangers outdoors in the dark and, unbidden, brought cleaning supplies to help us remove grafitti from a Jewish monument in Heidelberg.

A German Jewish immigrant from Russia told us about today’s Heidelberg Jewish community. I thank my German tutor of four years, Daniela. Her teaching let me connect with (and impress) German speakers. She worked with me to translate old family letters to better understand what my parents and grandparents lived through.

I thank my therapist for helping me handle the complex emotions stirred up by this trip.

I thank my children and their spouses, and my sister and my dad for supporting me along the way. That my dad, now almost 96, traveled with me vicariously was wonderful. He answered questions and spoke to me daily, adding color and context to our family’s journey to America.

And most of all, I’m beyond grateful to my supportive husband, my beschert, my soulmate, Jeffrey, a Litvak for whom Germany is a disconcerting and alien land. He drove me over 1,000 miles and put up with hearing hours and hours of German every day. This was an emotionally difficult trip for him. Married for 42 years, best friends for 43, I’m lucky to have him in my life.

At the end of a trip, I’m always happy to return to familiar sights, sounds and smells: to my own house, family, food and coffee. It’s hard to imagine never returning home, as my parents and so many immigrants experienced. The fear of being forced to live where you don’t speak the language is hard to grasp.

Thank you for reading my blog, commenting and sending me messages of support. It means a lot to me.

I hope that this journey inspires us all to have more empathy for those fleeing tyranny, and to welcome newcomers as they try to make a new life in a place they never wanted to call home.

I wish you all a safe journey.

—Nancy

The Brooklyn Bridge to Manhattan. Home sweet home. ❤️ To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Day #13: Another Province Heard From

Jeffrey here.

Our trip began with friends at their daughter’s lovely wedding in Austria. With Nancy.

There she is! In Germany.

Heidelberg Castle is on high. “Not my country, man!”

Nancy’s parents and grandparents thought they were German—until the hate and violence of their German neighbors forced them to flee. My grandparents, who escaped the Russian Empire 30 years earlier, had no such illusion of belonging.

To the Czar, my family in Lithuania, like all Jews, were execrable aliens. Still, Nancy and I are not so different. As in Nancy’s family, all my relatives who didn’t escape Europe by 1939 were murdered by the Germans and their allies. My kin died not in Germany, but in Belarus and Lithuania. All the military-age men in my family served in the U.S. Army in WW2, and thanks to the Germans, not all of them came home.

As I am the only member of our family without German roots, and I am Nancy’s only companion on this journey, Nancy asked me to share my point of view.

But first: ancient Heidelberg.

About to dine al fresco on one of the picturesque town squares. It’s a beautiful university town.

Jews lived here since at least the 1200s—except during periodic mass murders and expulsions. You know the drill.

And they live here again. A synagogue was built in 1994. It has about 400 members, almost all of whom are refugees from the former Soviet Union.

Caretaker Lemuel, whom the Soviets named Leonid, outside the Heidelberg synagogue.

The synagogue sanctuary. Jews from the east found a haven here. Jews with deep roots in Germany, like Nancy’s family, don’t live in Germany anymore.

Nancy’s family didn’t live in Heidelberg at all. So for us, being here was a bit of a rest. There are no family sites to see. No cemeteries with Freund/Steinberger/Grünstein ancestors. No inherited memories. To a greater extent than in our prior stops, we could just . . . be.

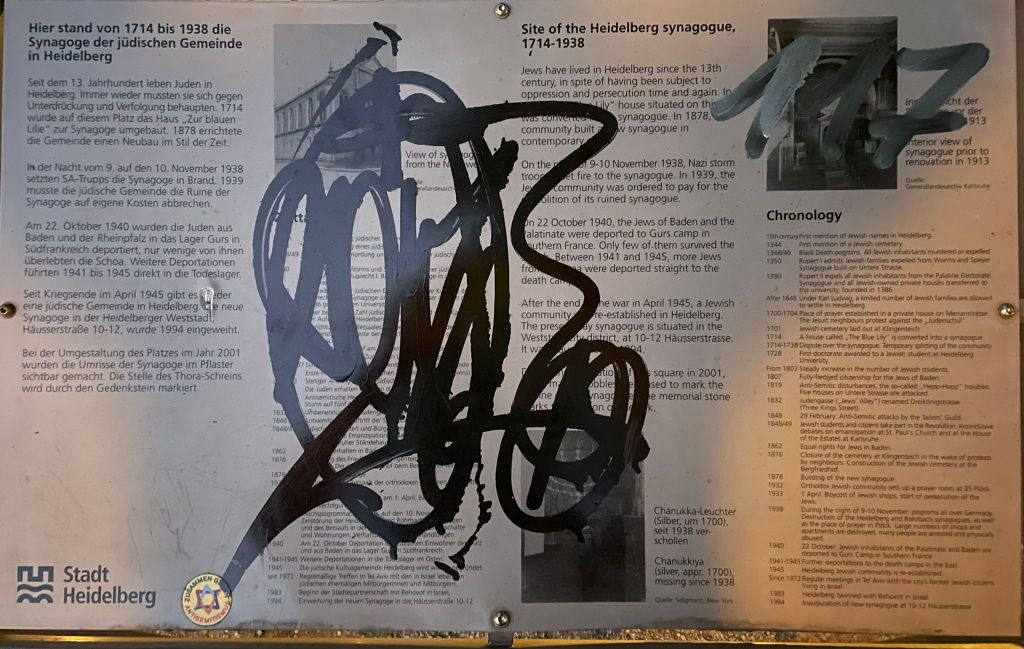

Still, Jews haunt this city. There are monuments.

“On This Place on 10 November 1938 a Wicked Hand Destroyed the Heidelberg Synagogue.” Outside of Israel, anything Jewish is likely to be vandalized, of course.

This was deliberate. Happily, there’s a silver lining to this vandalism of the site of the former Heidelberg synagogue.

Melina lives nearby. She saw Nancy and me trying to clean the sign with hand sanitizer and tissues. She joined us with powerful cleaners and paper towels to do a proper job. Kind Melina is from the Alsfeld area, as was Nancy’s mother’s family. Melina isn’t obsessed with the past. But she knows it, has learned from it, and wants others to learn too.

Here are my early thoughts on our exploration of Nancy’s roots.

This trip was difficult for me. Every day I saw something that overwhelmed my emotions. Every day I visited sites where terrible things were done to Jews in Germany. Every day I felt a mixture of horror, sadness, anger—and gratitude to the Germans who by acknowledging their history, show their love for humanity and their regret for what their families and neighbors had done.

My experience isn’t far different from when I biked through the Deep South of the USA and saw monuments to black American victims of white lynch mobs.

It took 110 years (!) for this plaque to be erected after a racist mob murdered an innocent man in 1906.

“No one was ever charged for the lynching of Bunk Richardson” from this railroad trestle in Gadsden, Alabama. Horror, sadness, anger—and gratitude. It’s a lot to process in America. And in Germany.

These emotions—plus the disconnect between the richness and beauty of this country, the kindness I see in the people I meet, and the horrors my people and others suffered at German hands—make Germany a hard place for me.

A hard place. Yet it’s a good place.

A few summers ago in a hot NYC subway car, a loud German tourist complained that the subway in Munich was much better than the NYC system. I silenced his obnoxious boasts by reminding him that his city’s facility was newer and better . . . because the USA bombed the old one. A new subway, and a new and more humane Germany, arose from the wreckage of WW2.

I think of this as I watch America’s recent slide toward fascism, never mind the deterioration of our infrastructure.

I ponder Thomas Jefferson’s assertion that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

I fear that blood might be shed in America by the hard-right cult of today’s pretend patriots who trample our Declaration of Independence and our Constitution. They imagine as tyrants the honorable American officials who obey the law.

And I wonder whether we will learn from today’s Germans. With our help, since WW2 they have largely if imperfectly faced up to their history, and built a society in some ways better than our own.

We ended our German adventure with a stop at Castle Frankenstein, near Darmstadt.

Our plane leaves tomorrow for NYC. Here’s hoping Nancy lets the monster out of the castle in time! To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Day #12 – Where Alsfeld Babies Come From

A stork plaque marks the fountain where the bird delivers babies. My mother was deposited here in 1920. L to R: me, Claudia, Daniela. Here in my mother’s home town, we were grateful to meet Daniela and Claudia, who spoke to us about Alsfeld history and gave us a wonderful tour. They are passionate about remembering and learning from the past.

At dinner we were joined by Aegidus and Joachim. All of us were born after WW2. We had a lively conversation about how our lives were affected by German parents who had spent the war in various roles on several continents. Our shared family histories forged a link of respect and friendship.

Left to right: our new friends Aegidius, Claudia, Joachim; non-German Jeffrey, and me. In their scant spare time, Claudia and Joachim have created a museum called Speier Haus to educate children about Jewish life and the destruction of a Jewish family during the Nazi era. I will tell you more about it in a later post.

Aegidius works for the Catholic church and organized a memorial ceremony on 9/11 for which I made a video that you can watch by clicking here.

We had a delicious afternoon lunch with our dear friends from the Dittmar family. The late Heinz took up the task of preserving the history of Alsfeld’s vanished Jewish community. L to R: Anna, friend of Heinz’s grandson David; Marga, Heinz’s widow; David; Marga’s sister Erika; Heinz’s daughter Christiane; and me.

Alsfeld dinner. L to R: Justin, Monika, Arnulf, Veronika and me. Monika, a journalist, has helped me with family history through her connections with those involved in preserving Jewish history in Germany.

My grandfather Adolf was born and named before, um, that other Adolf. My grandfather was a German soldier during WW1. He became a leader in the Alsfeld synagogue. My large Steinberger family lived for hundreds of years in Alsfeld and the neighboring villages.

Grandfather Adolf

The Steinberger house at 28 Alice Strasse in the 1930s

The Steinberger house today

My grandmother Rosi Grünstein Steinberger’s 1930 driver license; she was very proud of it. Hitler’s brown shirts were marching in Alsfeld even before Hitler took power in 1933. The photo below is from 1932. It was a scary time for my grandparents and all the Jews. My mother remembers the Nazi songs with lyrics like “When Jewish blood spurts off the knife, things will be twice as good”.

Booted Alsfeld Nazis marching in 1932.

Alsfelders “heiling” in the Alsfeld main square. My grandfather was a successful manufacturer of workers’ clothing. He had many employees, including two salesmen who drove Mercedes cars. The advertisement below appeared in the local newspaper.

“Steinberger & Co., Alsfeld (Hesse) • Machine Made Clothing • Tel. No. 46 • Specialties: Work and Professional Clothes, Windbreakers, Sport- and Lodenkonfektion [a special fabric] • Ask For an Offer or a Selection!” Early in 1933, one of the salesmen warned my grandfather that the Nazis were looking for him and that he needed to leave immediately. Adolf took a train to a neighboring town. That evening, Nazis came to the house, fired a bullet into the door, and extorted money from my grandmother. Adolf and Rosi got the message. Alsfeld and Germany, home to my family for centuries, no longer was safe for Jews.

Before summer’s end, Adolf and Rosi, their daughters Irmgard (who became my mother in New Jersey 22 years later) and Charlotte, moved to Haifa in what is now Israel. Alsfeld Jews, including others in the family, thought my grandfather was crazy for leaving. They believed they were Germans and that fascism soon would burn out or blow over.

They weren’t, and it didn’t. A few years later, all Alsfeld Jews had either fled the town, or were murdered. All of them.

L to R: my mother Irmgard, her mother Rosi and my aunt Charlotte (my mother’s sister) in Alsfeld in 1933, just before they emigrated. My Alsfelder great aunt Theresa Steinberger Strauss and her husband Markus Strauss waited too long. They are remembered with Stolpersteins (stumbling stones) in front of what was their house. They were deported in 1941 and murdered in the Lodz concentration camp, he at age 60 and she a bit younger; the exact date of her murder is unknown.

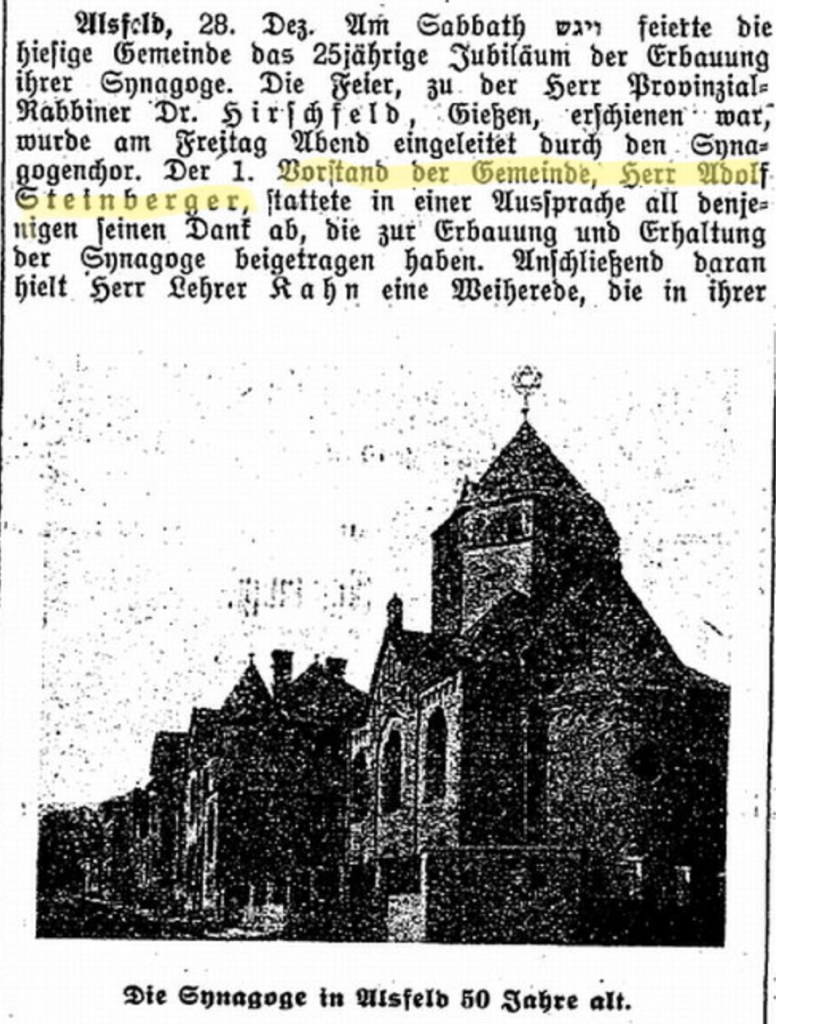

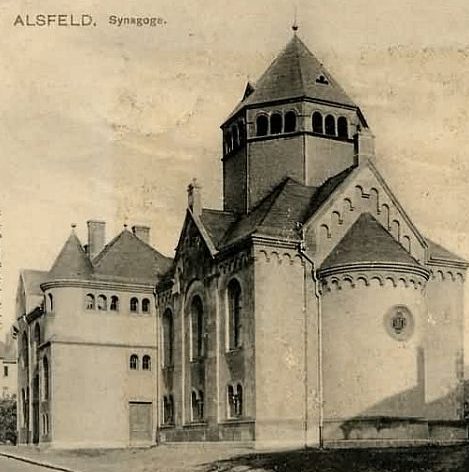

Stolpersteins for my great aunt and great uncle. The Steinberger family already was in Haifa when the Alsfeld synagogue was gutted by fire on Kristallnacht (9 November 1938). The local newspaper had reported in 1930 that my grandfather spoke in the synagogue on the building’s 50th anniversary. I have highlighted the section on my grandfather, Adolf Steinberger, head of the Jewish community.

“The synagogue in Alsfeld is 50 years old.” The synagogue was beautiful inside and out.

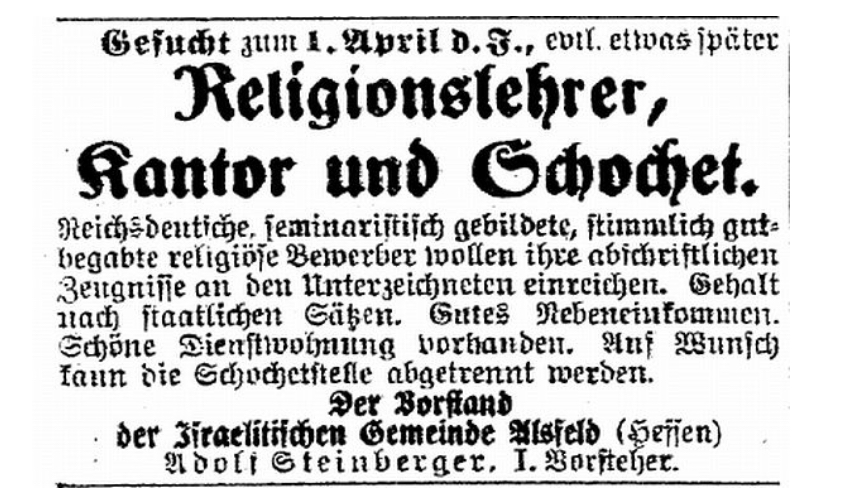

Adolf chaired the board of the synagogue in 1924 and was in charge of finding a teacher, cantor and kosher butcher. His name appears at the bottom of this incredible newspaper advertisement, translated below.

“Wanted for April 1 or later, religious teacher, cantor and and kosher butcher who is seminary educated, vocally gifted. Must submit official religious certificates to the undersigned. Good side income. Salary based on state rates. Beautiful service apartment available. On request, kosher butcher can be hired separately. • The Board of Directors of the Jewish Community in Alsfeld (Hesse) • Adolf Steinberger, chairman.”

The synagogue building was taken by others after the 1938 attack and fire. It currently is abandoned. The current owners have refused to sell to Alsfelders who want to restore the building as part synagogue, part travelers’ hostel. From his haven in Haifa, my grandfather arranged for the immigration of every one of his Jewish workers. The family house and factory in Alsfeld were “sold” for whatever pittance ”Aryan” buyers would offer.

A regional museum in Alsfeld is under construction. A temporary display includes a 7-compartment box of unknown purpose. The names of grandfather Adolf and great uncle Julius are written on the obverse.

The back of the box, which must have hung from a wall.

The front of the box with my relatives’ names circled in blue. Was the box used in connection with Torah honors? Donations?

In 1938, five years after arriving, the family became citizens of British Palestine. This document shows my mother’s name had changed from the very German Irmgard to the Hebrew name Yehudit (later Judith in the USA).

British Palestine passport Life in Haifa was difficult for the Steinbergers. They were used to different foods, climate, business practices, a different language and higher standard of living. Grandfather Adolf no longer was an important man well-known to his community; he wrote back to Alsfeld that no one had been waiting in Haifa to roll out the red carpet for them. Like immigrants today, they had to make their own way.

Haifa’s people were not particularly religiously observant. My grandfather was astonished that Jewish people there smoked on the Sabbath.

But Haifa was safe. The Steinbergers made friends in the Jewish and Arab communities, and with Jewish refugees from Germany who continued to arrive.

Thus ended the Steinbergers’ lives in Alsfeld. But the connection is not entirely broken. The work of our Alsfeld friends to preserve Jewish history, and my visit to see them and their work, has continued the link for another generation.

My mother and me in 2010. That year she told me many family stories.

Alsfeld today -

Day #11 – Freund means Friend: Aschaffenburg

[First, some housekeeping: To see my latest post, and to scroll back through prior posts, always go to nancysgermanyroots.com/home .]

I have been interested in our family history for decades, asking my parents to share their stories. Getting a feeling for how my relatives lived fascinates me. Understanding the Nazi period is hard. As my family lived in Germany from the 1600’s (if not earlier) until 1942 (when the last of my relatives who had not escaped was murdered), much of the genealogical information is in old Gothic German script and is hard even for natives to read.

Some Germans have dedicated themselves to recording the Jewish experience so it is not forgotten. They teach children, and find and post old documents online. Fortunately, I have met some of these warm, intelligent, selfless people. They are Freunds indeed. As many of you know, Freund (“friend” in German) is my maiden name. (Americans have trouble pronouncing it; my mother would say, ”just add an ‘n’ to the last name of Sigmund Freud.”)

One Freundin is my friend, Iris. We were introduced via email and met in person on this trip. Bilingual in German and English, Iris has helped many Jews with translations and tours.

Without Iris, my research on cousin Louis Joseph (the savior who helped my family when America was ready to bar the door and God was silent) would not have been possible. It is Iris who found and translated the missing family link.

Iris is kind, smart, understated and modest. She arranged and joined us on several private family history tours and took us herself on a grand tour of Aschaffenburg.

Aschaffenburg, a beautiful city on the River Main (say “mine”), has a big castle: Schloss Johannisburg. Constructed of red sandstone, it was erected between 1605 and 1614.

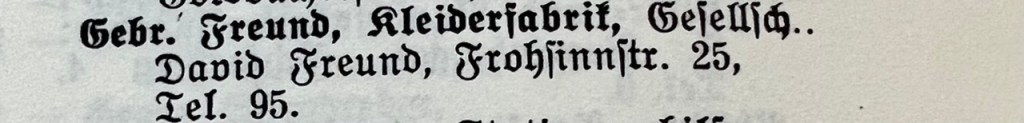

All these Freunds emigrated to New York or Chicago. Emanuel had his own Aschaffenburg engineering business. Fred and David ran the Brothers Freund clothing factory in town. I met many of them. Now everyone in this photo has passed away. Iris has a 1920 phone book that lists the Freund family. It was eerie to see so many familiar names written in old German with their residences, occupations and phone numbers. Call 599 for my great uncle the engineer!

I have added blue arrows indicating David Freund, Kleiderfabrik (clothing factory), Emanuel Freund (engineering diploma) and Gebruder Freund (Brothers Freund).

Aschaffenburg had a Jewish community for centuries, from the 1300’s. A beautiful synagogue was built in 1892 in the Moorish style. The synagogue was burned to the ground by German Nazis and their supporters on Reichspogromnacht or Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass, November 9-10, 1938). The Jewish community was forced to pay for the demolition of the remnants.

A monument and stand of sycamores are on the site.

“‘Oh but you can’t bring the dead to life if love doesn’t do it.’ [Friedrich] Hölderlin [1770-1843] • Here stood the Jewish religious community that on 9 November 1938 was destroyed by criminal hands.”

November 1938: Aschaffenburg synagogue destroyed.

The Pompejanum was built as a Roman style villa from Pompeii in the 19th century. It was commissioned by King Ludwig I in the 1840’s. It is now a museum.

Aschaffenburg’s town center has old timber buildings. There are many sites and museums that we did not have time to see.

The Rathaus is modern.

Grapes grow along the Main River. Wouldn’t that be nice in NYC! In other times, Iris and I would be neighbors as well as friends. Delightful Iris would have been a Freundin of her contemporaries in the Freund family, were my cousins still in Aschaffenburg.

Sadly, there are no Freunds here.

There is no Jewish community here.

Iris and I will remain pen pals and Freunds.

-

Day #10 – Grandma’s Shoe Store in Miltenberg and Kaffee und Kuchen (coffee and cake)

Beautiful Miltenberg along the River Main (rhymes with ”mine”) Miltenberg is a beautiful medieval town. Cruise ships dock for the day so tourists can walk in the woods, see the castle and shop along the old cobblestoned streets. Both my parents came here as children to visit their loving grandmother Selma.

My skinny mother was sent to Cafe Sel to eat Schlag (cream) off a spoon. It was there that we stopped for cake. I was flooded with memories of my New York grandmother as I ate Zwetschgenkuchen (plum cake). Jeffrey had apple strudel (I had a taste), another of her specialties.

Cafe Sel

Plum cake with Schlag (cream) and apple strudel with vanilla sauce. But I am getting ahead of myself.

We were greeted in Miltenberg by the mayor and his deputy, and gifted with a monogrammed umbrella against the rain.

Deputy Mayor, Mayor, and me.

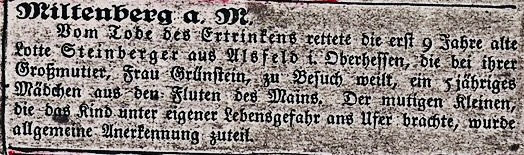

This old fountain formerly was used for drinking water. At age nine, my Aunt Charlotte, whose turn it was to visit her Grandma Selma, saved a five year old girl, Elizabeth, from drowning in the river. The newspaper in Miltenberg carried the story in 1932. After the Nazis took power in 1933, my aunt was permitted to stay in the regular school because of her heroism. (She, my mother, and their parents fled Germany for British Palestine later that year.)

This is the original newspaper article that reported Charlotte’s bravery.

My young aunt’s photo made the paper: ”Lotte Steinberger (Alsfeld), nine year old Jewish lifesaver.” We were welcomed in Miltenberg by Elizabeth’s family! Elizabeth’s nieces Dorothea and Ulrike, together with local Jewish historians Gabriele and Georg and other locals, gave us a tour of the town and the Jewish and family landmarks.

Great-Grandmother Selma ran a Miltenberg shoe store after her husband died. By all accounts, she was an excellent businesswoman and a loving grandmother. Today, the store is a pizzeria.

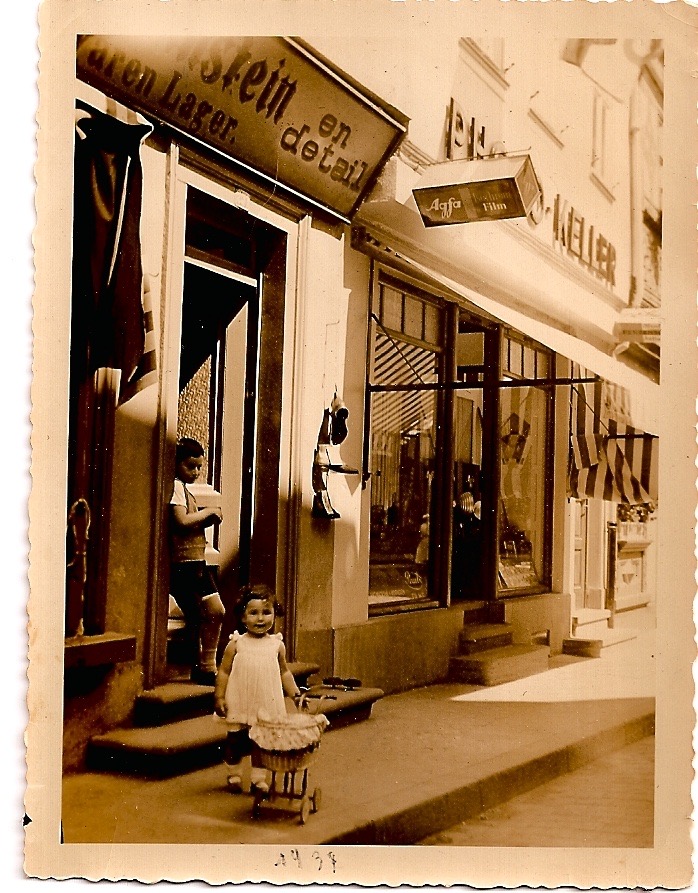

This is Great-Grandma’s shoe store in 1934. She emigrated to Haifa in 1937. My father stands in the doorway as he looks at his cousin Frieda.

Great-grandma’s shoe store today My parents talked lovingly of the freedom their grandma gave them to wander in this forest, something I never had done until yesterday.

In the Wald (woods). At the edge of the woods, outside the city wall, lies the old Jewish cemetery where several of my forebears are buried. The grass is cut twice a year.

Miltenberg’s Jewish cemetery.

Here is our Miltenberg tour group. L to R: Georg, Gabriele, Iris, Nancy, Jeffrey, Ulrike, Toni. From the fountain we walked to the top of the hill, overlooking the river.

We walked by one of what once were three local synagogues (now there are none), saw salvaged Jewish religious objects in the local museum, and stopped at some of the Stolperstein (“stumbling stones”) that memorialize a few of the Miltenberg Jews who were deported and murdered.

Stolpersteines are 3.9 inch concrete cubes set into sidewalks outside Jews’ former residences. The cubes are topped with brass plates inscribed with the names and fates of Jews murdered in the name of the 1933-45 German regime. One is meant to stumble over the blocks and remember the victims.

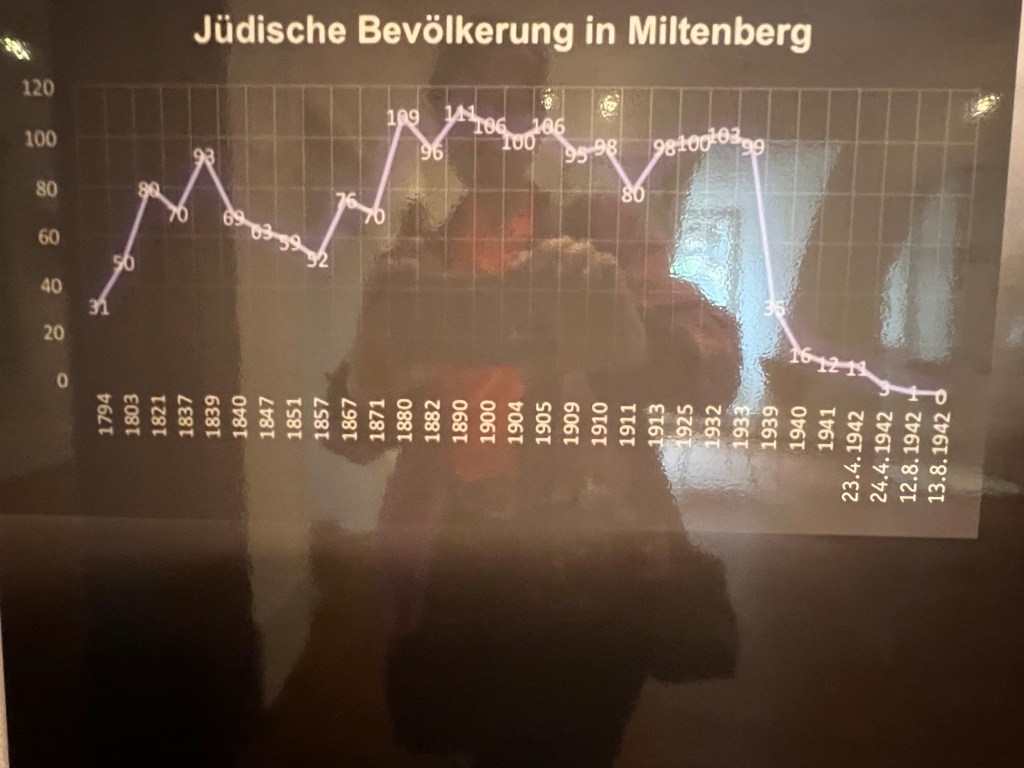

This is the Jewish population year by year in Miltenberg beginning in 1794. The number reached zero on 13 August 1942.

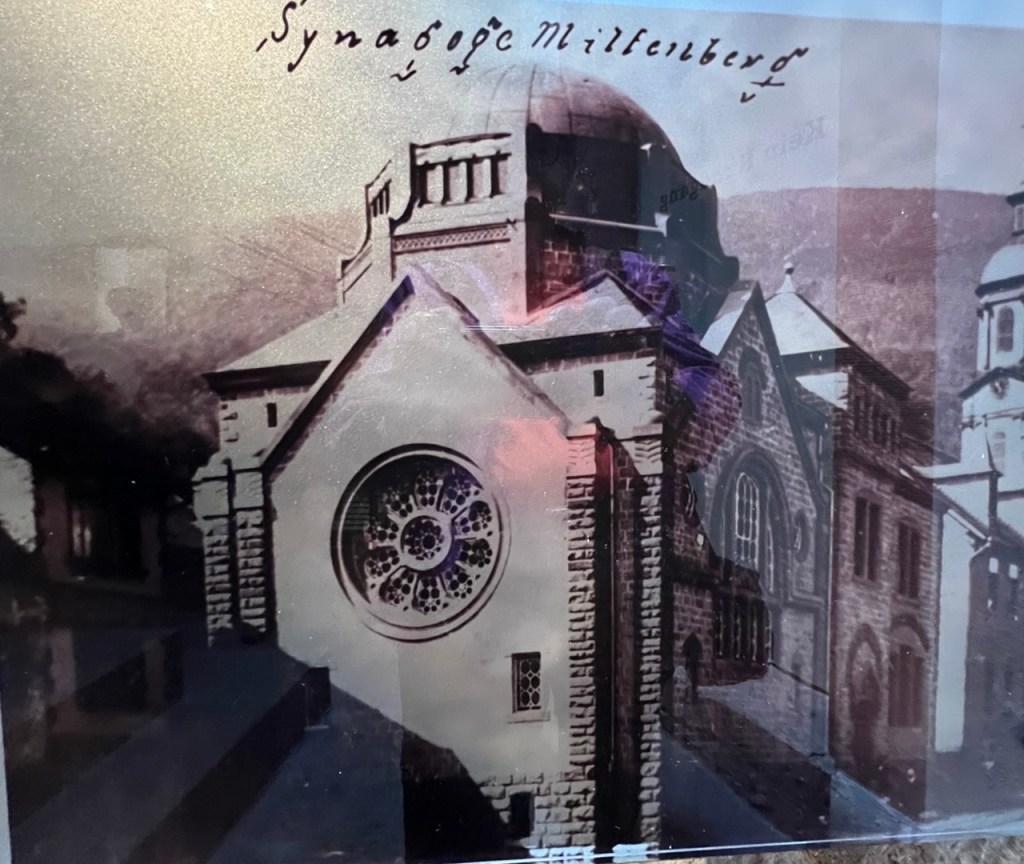

This Miltenberg synagogue was destroyed on Kristallnacht, 9 November 1938.

This former synagogue has no signage mentioning the building’s past.

We said goodbye to Miltenberg, a beautiful small town in Bavaria, home to my grandparents and other forebears, a place of joy, love and freedom for my parents—until 1933. Today no Jews live in this town.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Day #9 – Our Savior from Reichelsheim: Louis Joseph

My Freund family from Nuremberg was saved from certain death by a distant cousin, Louis Joseph. Though everyone in the family knew his name, it took me almost a year to figure out our exact relationship.

Beautiful Reichelsheim Louis arrived in New York in 1893 at age 16 from Reichelsheim, with two teenaged cousins, as third class passengers. The Joseph boys had no visas. In those days, they were not required. Louis had older brothers, so he had a bleak future in Reichelsheim: in Germany, only the eldest son inherited the family house and land. Poverty pushed many people abroad in that era, not just the Jews.

Louis became a well-paid manager at the Wilson Meat Packing Company, and in 1901, a U.S. citizen.

Louis Joseph photo from US Passport application In 1936, the Jewish men in Nuremberg (including my grandfather) were arrested and forced to run around a track until they dropped from exhaustion. Someone secured my grandfather’s release, perhaps through a bribe. His trauma was the impetus my family needed to leave.

Among other requirements for U.S. visas, my grandfather had to show that he and his family would not become ”a public charge”. He wrote to Louis, whose mother was a Freund; even so, Louis never had met my grandfather. No matter. Louis provided an affidavit of support, and later sent a bankbook that my grandfather could show to the U.S. consul as evidence of financial means. Louis provided such documents to any relative and anyone from his home town who asked.

I created a short photo essay journal on Louis’s life and personally delivered a copy of the book to the Rathaus in Reichelsheim to be sure that they knew the story of their native son. I also have thanked Louis’s distant relatives in Australia, Chicago and New York, as he had no children.

Our journey to Reichelsheim began when I wrote to the mayor (Bürgermeister) who put me in touch with Gerd Lode, the former mayor, who has been documenting the Jewish history of Reichelsheim for 18 years. Gerd gave us a warm welcome and an introduction to the current mayor. We were given a book with the history of the Jews in the town, Not to be Forgotten: The Jews in Reichelsheim, a list of all the Jewish families that once lived there, and a tour of the pretty town.

Gerd and me

Gerd, Bürgermeister Stefan Lopinsky and me The Jospeh family was large. One branch owned a matzah factory. Another branch were cattle dealers. They lived in harmony with their non-Jewish neighbors. The town has not forgotten them, and Gerd has done all he can to document what is knowable, to ensure that the Jewish cemetery is kept up, and to see that the Jewish community’s history is preserved and remembered. We are impressed and grateful.

White building was the matzah factory, the dark building the butcher shop.

“Take good care of your soul, that all your life you don’t forget the story that your eyes have seen, and tell it to your children. In memory of our Jewish neighbors who were victims of the Third Reich’s violent reign. —The Community of Reichelsheim”

Not all the Joseph family survived. These plaques are set into the sidewalk in front of the house where they lived. ”Deported” ”Dead” ”Removed” “Dead” ”Deported” “Murdered”

And tomorrow, we tell the story of these fabulous desserts. To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Day #8 – Tears of Sorrow and Triumph

I stood where Hitler stood to view mass Nuremberg rallies. Now it overlooks the route of an upcoming car race. Zeppelin Field was the site of the Nazi’s biggest rallies and where we started our day on Wednesday. It was chilling and brought tears to my eyes as I stood on the same platform where Hitler roused hundreds of thousands of stiff-arm saluting Nazi supporters. The stadium design was based on the ancient Greek Pergamon Altar and was originally topped with a towering swastika, which was blown up by the U.S. Army after capturing Nuremberg in April 1945.

Click here to watch a video of its destruction.

Clowning around or gesturing on the platform is illegal. While the Nazis rallied, the Nuremberg Jewish population would lock their doors, close their window shades and stay home. When the rallies took place, even before Hitler took power, my father often was sent to his grandmother’s house in a nearby town. Mixed with my fear and sadness was a little triumph: Hitler and his murderous empire were destroyed, and I, a Jewish woman, stood free atop his ruins.

We then drove to Aschaffenburg where we met my pen pal and friend, Iris, with whom I have lively email conversations. She has been hugely helpful in my genealogy work. She’s a person of thought and ideas, a wonderful tour guide, and an outstanding cook.

Iris and me. Iris made us a real Hessian dinner. Hesse is just north of Frankfurt, where my mother is from. More on that later.

Left to right, a woman who reads old German, Iris, me, and the Mayor of Kleinwallstadt. Our first stop was Kleinwallstadt (“small walled city”), the city to which the Freund family traces its roots to 1773. My great-great-grandfather, Liebmann, was a prosperous businessman who ran a dry goods store and raised a large family in a big house next to the business. Liebmann also was a leader of the Jewish community.

Standing in front of where my forebears lived brings the family history to life. I imagine meeting my relatives and get a feeling of the times. Jews from this town had to schlep miles uphill, following a horse drawn carriage, to bury their dead in the nearby town of Obernau.

Liebmann’s house on the left in brick and the store on the right in white. The mayor (Bürgermeister) of Kleinwallstadt welcomed us warmly and introduced us to a musician and accountant, Achim Albert, a history buff who on his own time has been documenting the Jewish history of Kleinwallstadt for 35 years. He is dedicated to remembering the Jewish famiies and history and we were impressed and grateful to him. Achim showed us a document signed by my great uncle in 1917 regarding the costs of electrifying the Catholic church in town. Interestingly, this uncle used his engineering expertise in Chicago after he emigrated to the USA.

Achim walked us to Liebmann’s house and business. Today the house has six apartments. We could see holes in the doorposts where a mezuzah once hung.

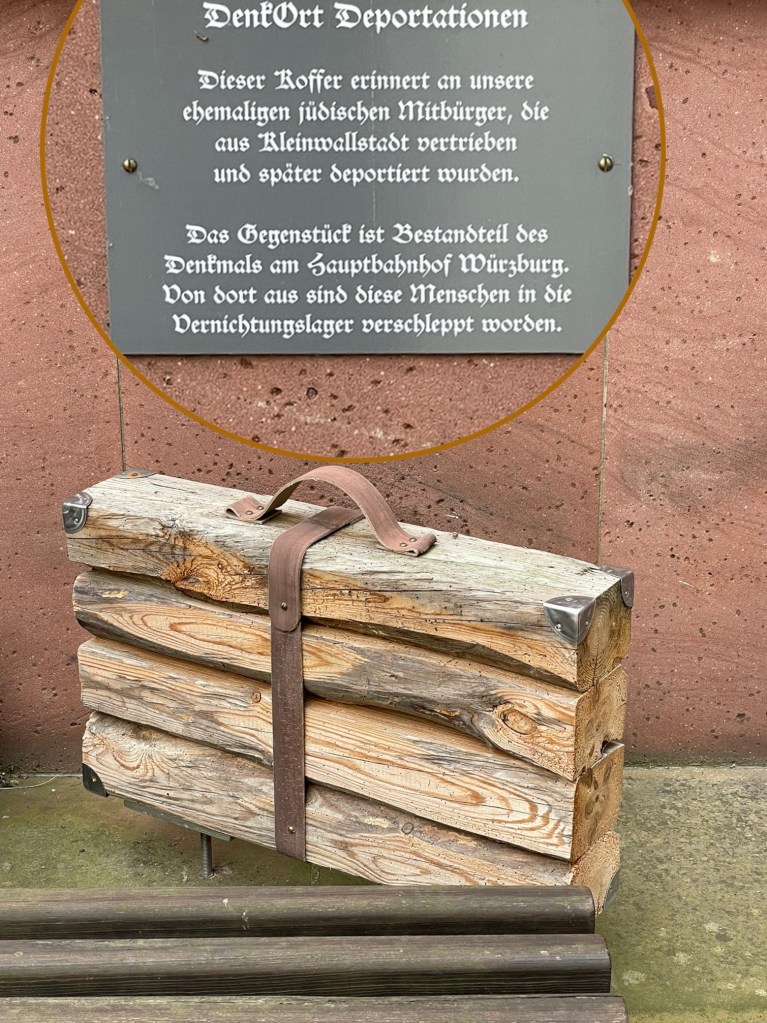

Just outside the Rathaus and is a memorial to the Jews of Kleinwallstadt. A suitcase at a fountain symbolizes the expulsion and murder of the Jews who remained in the town after Hitler came to power.

Achim takes us on a walking tour

Remember and be warned Memorial outside the Rathaus, a powerful image and remembrance. The plaque above right says: “In Kleinwallstadt until 1938 there was a Jewish community and synagogue at 11 Ratgasse Street. This is a reminder and a warning.” We walked past the building that housed a Jewish day school from 1899-1917 and saw a contract signed by Liebmann Freund on behalf of the Jewish community to rent an apartment with heat (a big deal) to a Jewish teacher who was hired to educate up to 14 students. There still is Hebrew above the door.

Above and below: Jewish school in Kleinwallstadt.

The teacher lived in an apartment on the top floor. Before the Nazi era, Jews were well integrated into the Kleinwallstadt community. Achim gave us an example: Jewish and Christian butchers would share cows, the kosher butcher using the kosher parts, and the non-kosher butcher using the rest.

The Kleinwallstadt synagogue was not burned down on Kristallnacht (November 9, 1938) because the last Jews had just left town and the building had been ”bought” by a non-Jew. Achim knew when the last Jews left because the new mayor at the time, an enthusiastic Nazi who wanted the town to be ”Jew-free”, posted the number of Jews living in town on a placard at the railroad station. Just before Kristallnacht, the number was reduced from two, to zero.

The original color of this 18th century synagogue building was not pink. We met the current owner of what had been the synagogue, the son of the man who ”bought” the building as the Jews were running for their lives.

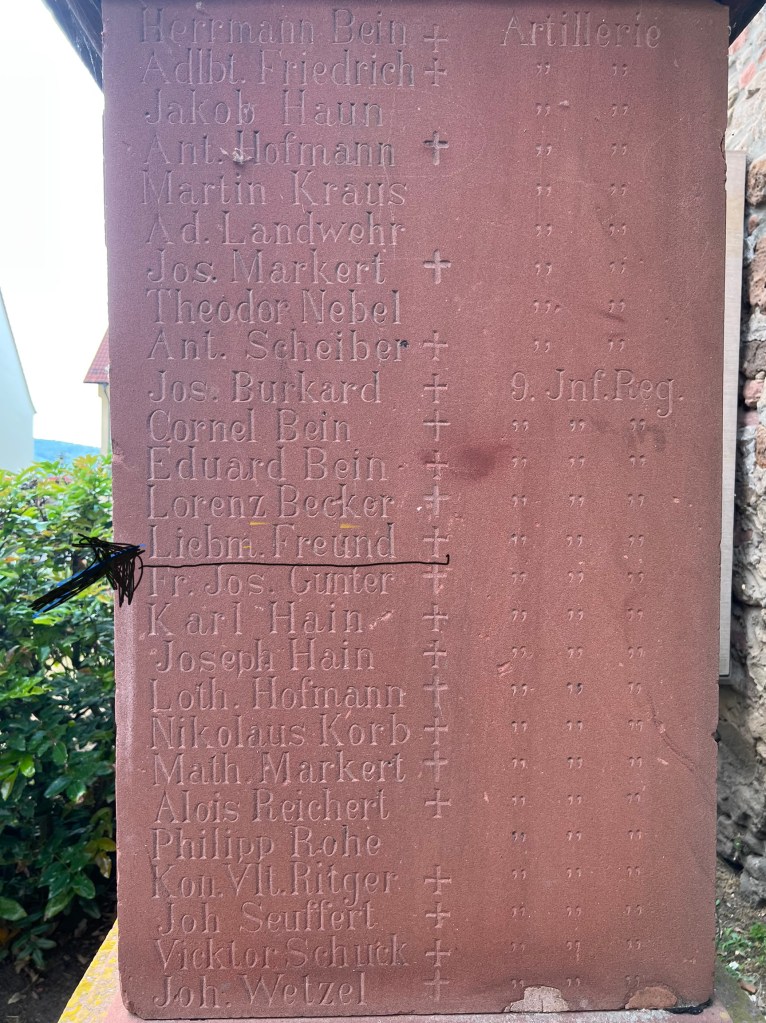

The “buyer’s” son is the man at right. He and his wife (talking to me at left) removed the mikva from the synagogue basement. They didn’t want ”living waters” below their residence. My great-grandfather served as a soldier in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War. His name is on a stone monument with other soldiers from Kleinwallstadt.

Liebmann Freund served in the 9th Infantry Regiment. He contributed to Prussia’s victory, which set the stage for WW1, which set the stage for the rise of the Nazis and WW2. To stand in front of the house where my Freund great-grandfather and his family lived, the synagogue where he prayed and school where he sent his children was emotional. My grandfather went to that school as a child. This is where my Freund family comes from.

We ended the day Aschaffenburg (A’burg for short) where Iris treated us to a tour. As it is getting late here in A’burg, I will write about A’burg and our trip to Reichelsheim in my next post. Bear with me as I fall behind.

But first a coincidence. The City Hotel in A’burg where we are staying is at Frohsinnstrasse 23. Iris has a 1922 phone directory from A’burg showing the Brother Freund clothing factory at Frohsinnstrasse 25! Assuming the building numbers haven’t changed, I write this next door to the store that two of my great uncles managed. It kinda blows my mind.

Freund Brothers, Clothing factory. Phone number is 95.

No. 25 is the old brown building to the right of City-Hotel Aschaffenburg. To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Day #7 – A Day Off – On Freund Street

We had a very busy day and it is late in Germany. I will post the next two days’ adventures tomorrow.

Me on Freund Street in Aschaffenburg. How cool is that! To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Day #6 -My Dad’s Tram 🚃 to School – Nuremberg!

Often I wonder what life was like for my forebears. Today I had a taste.

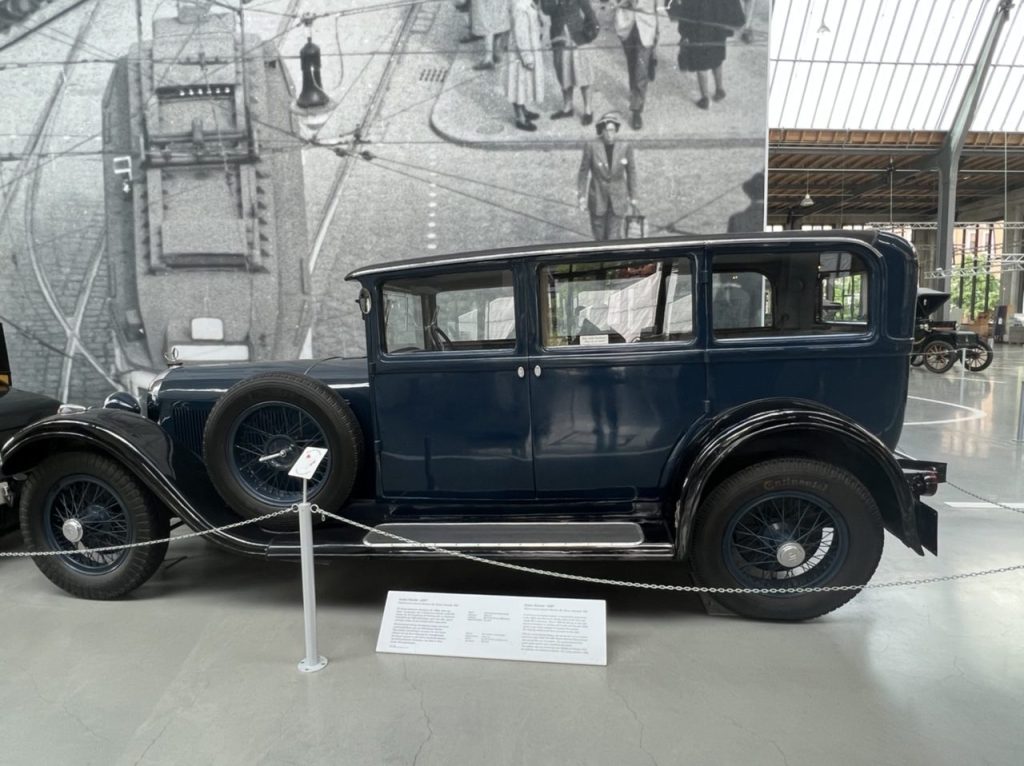

Inspired by our train-loving friend Art Bilenker, we decided to visit Munich’s transit museum (not my usual museum choice) just across from our hotel. There we saw a Nuremberg city tram, built in 1926, the year my father was born. (Remember the year: 1926!)

A museum worker, Christian, told us that we had crossed into a forbidden zone next to the tram. We explained that I wanted a close look because my father, like all Jewish children in 1936, had been expelled from public school in Nuremberg, forced to travel by tram every day to the Jewish school in neighboring Fürth.

Christian understood. He welcomed me warmly, fetched a key, opened a gate, and guided Jeffrey and me onto the tram!

Christian showed us the heaters under the seats, the box of sand used to keep the brakes effective, and a sign that reminded riders to keep the doors closed from October to April to conserve heat.

Sitting where my father may have sat.

Keep the doors shut

Sand to slow the brakes The museum has a huge collection of trains, bicycles, motorcycles, and cars.

A cool car from the 1930s.

My father is the little guy standing in front of his uncle and a similar sedan! We arrived in Nuremberg at lunchtime. Our first stop was the Lebkuchen Schmidt store. Schmidt has made these local spice cookie specialties since … 1926! At my father’s suggestion, we bought broken Lebkuchen without a tin, for the same great taste at a fraction of the cost.

Mmm! More is better. ”Not a diet food.”

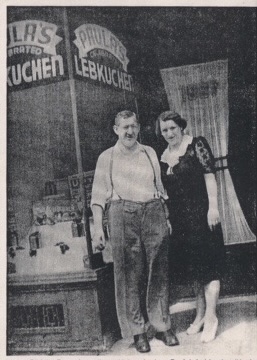

These are my grandparents in front of my grandmother’s Lebkuchen store in Washington Heights, New York City, in 1939. That is a story for another day.

It is said to be good luck to turn the golden ring attached to the Beautiful Fountain (Schöner Brunnen). The fountain brought fresh water to old Nuremberg.

The fountain was encased in concrete during WW2 to protect it from the Allied bombing that flattened most of Nuremberg.

Views of 1940s Nuremberg: left; pre-bombing; right, post-bombing. Beginning years before Hitler became chancellor, Nuremberg hosted many Nazi rallies. Some say that during WW2, it got what was coming to it.

After the war, Nuremberg was rebuilt, and German society was rebuilt, in ways that serve their people. Today this city and this country provide a good life for their people and resettle refugees rather than create them.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.