-

Essay #25 – Left Behind Aschaffenburg – May 17, 2023

Today we are in Aschaffenburg with our dear friend Iris. Iris volunteers with a local organization to digitize the history of Jewish families (complete with family trees, birth certificates and other documents). She even enters phone book information. A former English teacher, Iris is the main contact for English speakers who visit and she is a great tour guide. We met Iris last summer though we have been corresponding for years. How I wish we were neighbors.

Iris has opened her heart and her house to us. We demolished this delicious homemade strawberry cake with cream (Schlag in German) at the end of the day.

Iris and me. I get ahead of myself. Let’s go back to the start of our day now that you have seen the end.

Iris took us to a farmers’ market to shop for the dinner she will cook for us tomorrow night. Tomorrow is Ascension Day, a national holiday in Germany, and everything will be closed.

The sign on the bakery truck says “Since 1908”.

Jeffrey and I watched Iris shop. Note the white asparagus in the background. It was Freund/Heller laundry day, which is not an official German holiday.

All cash laundromat. I helped. Aschaffenburg is an important stop for me because many Freunds moved from little Kleinwallstadt (population 6,000), where yesterday we spoke to students, to busy Aschaffenburg (pop. 45,000 when my family lived here, 30,000 after WW2, 70,000 today).

Where did they live? What did they leave behind?

Great Uncle Emanuel Freund was a university educated engineer with a very successful family business called “The Brothers Freund” that provided electricity to towns and homes in the area. The business also sold cars and bicycles. Emmanuel (born 1882) lived in a big beautiful house with his wife Betty Fromm and three daughters.

Great uncle Emanuel’s house Emanuel and most of his family emigrated to Chicago at the eleventh hour, in 1939, where his engineering knowledge lit up houses and businesses. There is something poetic in this story: German Jews exiled and American cities light up. Despite frantic family efforts, the eldest daughter (Liselotte Siddy Solinger, born Freund) could not escape; their fellow Germans murdered her.

We walked the path Emanuel would have taken to work, all the while thinking of him and his family and the comfortable existence they had enjoyed before Hitler. Leaving their home was hard. I often wonder how I would have acted under these circumstances.

Iris and Jeffrey leading the way. Though I have been to Aschaffenburg several times, I never had been to the Jewish cemetery in the city itself. Iris showed us family graves that we had never seen. Dad participated on FaceTime.

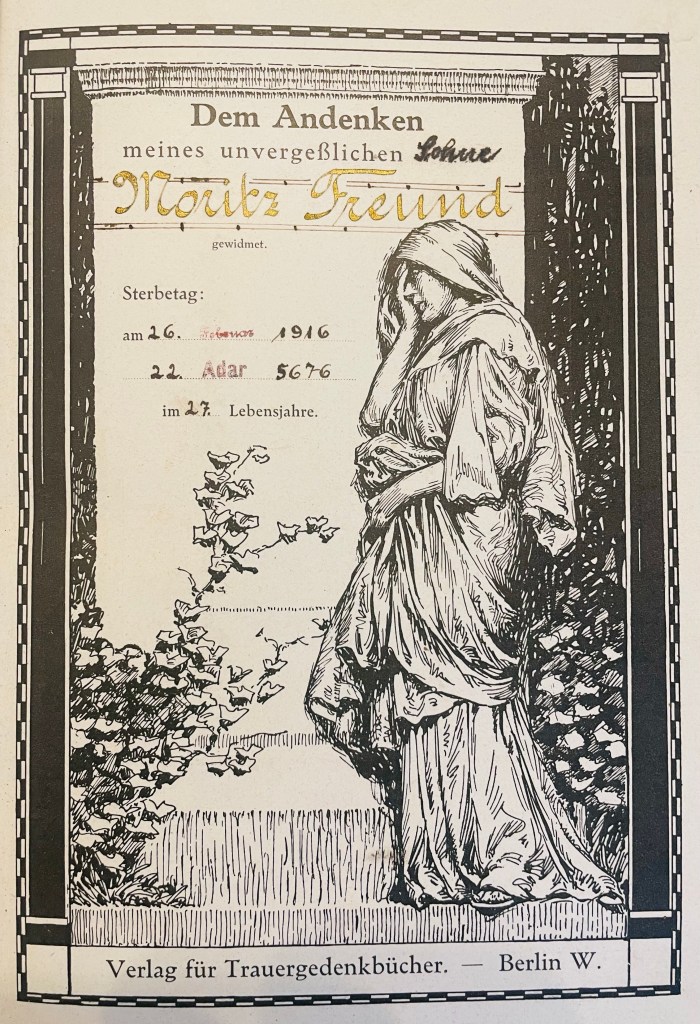

Emanuel was child number four of eleven children. My grandfather Hugo (kid #11) was his brother. Another brother, Moritz Freund (#9), died in France in 1916, fighting for his German Fatherland. Moritz’s parents were given a memorial book, shown below.

I stood at Moritz’s grave.

“Here lies in peace our loved and good son and brother Mr. Moritz Freund, born in Kleinwallstadt 14 November 1889, died in a field hospital in Carvin [France] 26 February 1916 as a field artillery soldier in the Royal Bavarian 17th Infantry Regiment.”

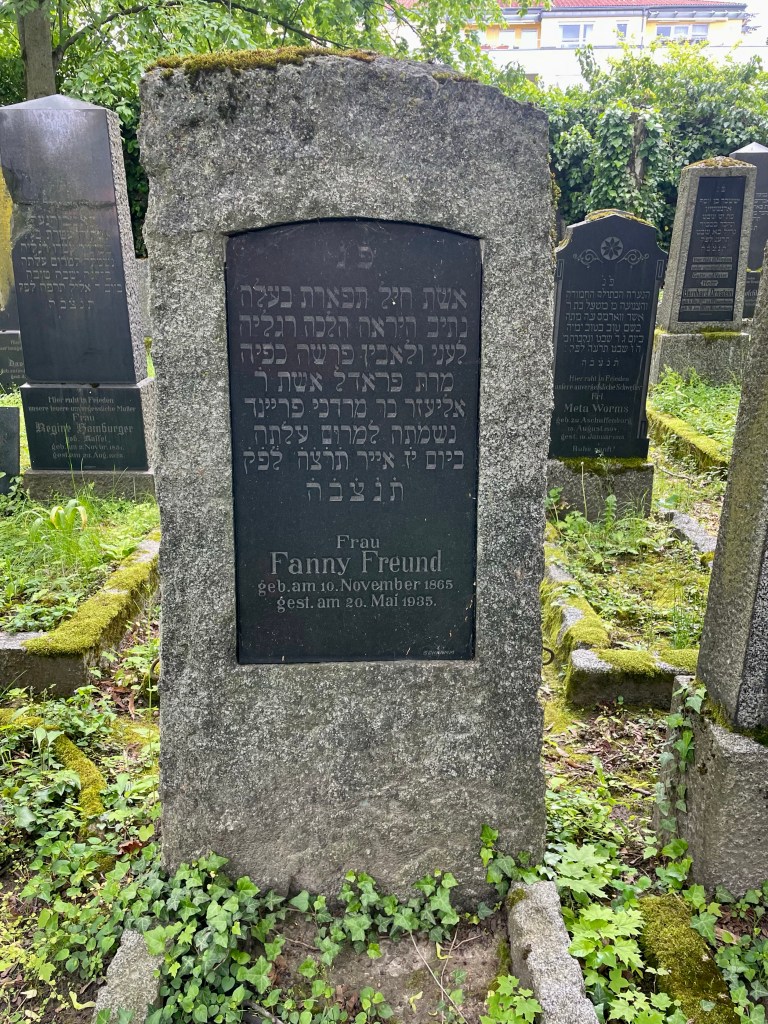

Memorial for the patriotic Jewish Germans of Aschaffenburg who lost their lives in WWI. Other family members are buried in this cemetery, including Fanny (born Kochland) and Lippmann Freund. This couple had one daughter, Irene Freund.

Born in Ichenhausen, Bavaria, in 1865, Fanny lived to see the Nazi rise to power before she died in 1935.

Fanny’s husband Lippmann Freund (1851-1915) was my first cousin thrice removed.

Irene Freund was murdered in Poland in 1942. What would my 19th Century Aschaffenburg family think of their American relative who came to photograph their gravesites and honor their lives.

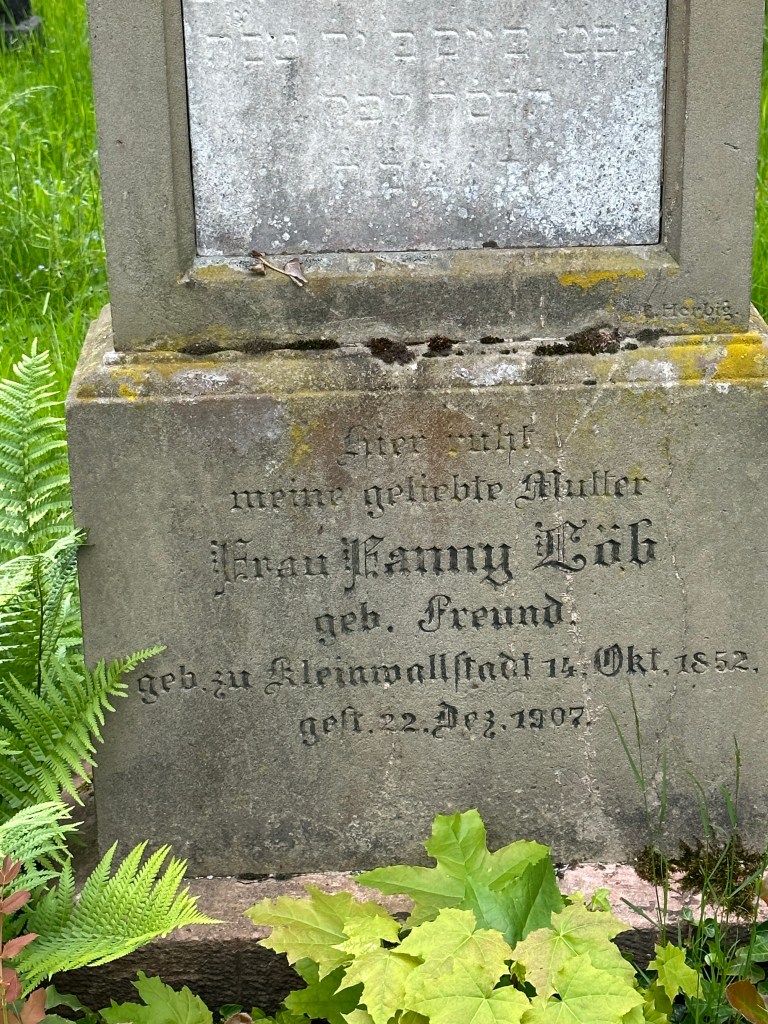

Fanny Löb (not to be confused with Fanny Freund), born in Kleinwallstadt, was my great-grandfather’s sister. In this same cemetery are graves of German soldiers who died in WWII. Some German soldiers were innocent victims of the Nazi regime. Not these men. They were in the SS.

Slave laborers from Eastern Europe who survived WWII are buried in this cemetery, near a memorial to WWI Russian prisoners of war.

The ashes of 103 Russian POWs of 1914-19 are buried here. No one on earth actually remembers any of these people. Time makes the horror seem distant. But it’s still horror.

Remembering the past is useless unless we learn from it, and apply that learning.

I hear the voice of my mother’s father Adolf Steinberger in 1933: “In a country where you have no rights, you cannot live.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt said on January 6, 1941, “Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere.”

What I saw today evoked my family’s suffering during and between the World Wars. I hope it inspires thoughts and actions, in me and in others, to help repair our broken world.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #24 – Smart in Kleinwallstadt & Elsenfeld – May 16, 2023

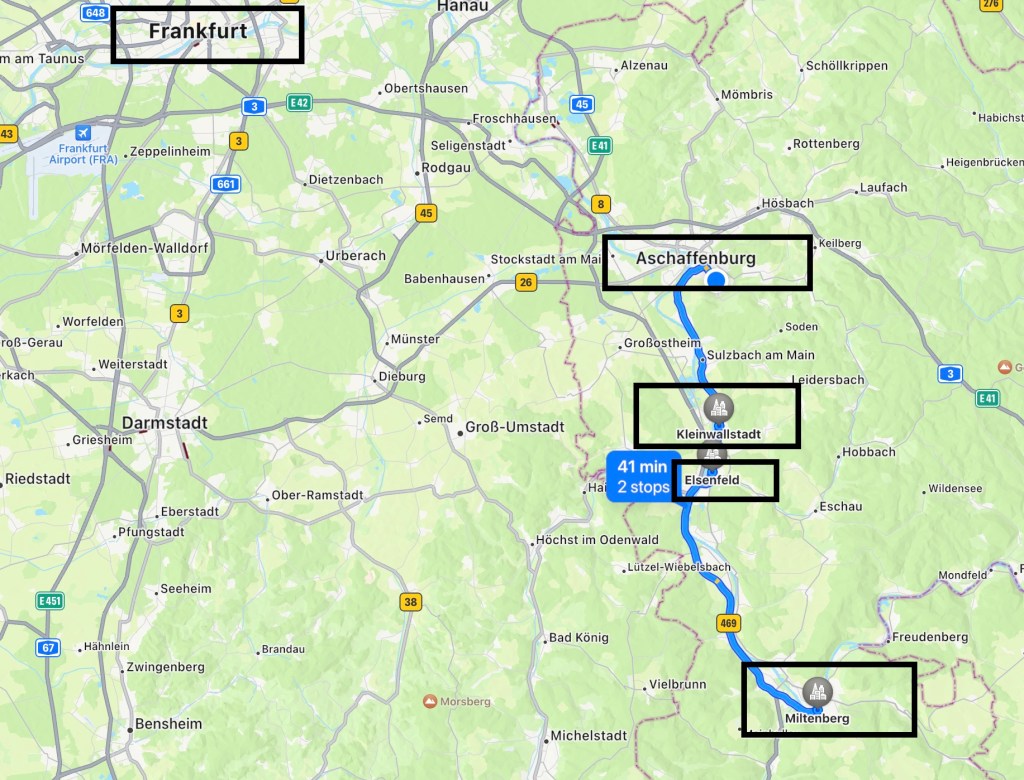

It was just a half hour drive from last night’s stay in Miltenberg to Kleinwallstadt.

Kleinwallstadt (population 6,000: “SmallWalledTown”) is where my Freund family lived from at least 1773, when German families began to have surnames. For centuries, the town had a thriving Jewish population. In the late 1890s, my great-grandfather was president of the synagogue and owned a successful dry goods store.

Achim Albert, the expert on the town’s Jewish history, greeted us.

Behind Achim is the old Kleinwallstadt Rathaus, or town hall.

Achim’s mother baked us an Oreo cookie cake. She didn’t know the Oreo’s national origin. Near Kleinwallstadt is Elsenfeld (population 9,000). These two towns are in Bavaria, the Deep South of Germany.

We might call these beautiful small villages one horse towns, though I saw two horses on the way in.

Driving into Kleinwallstadt But don’t be fooled. The high school students in these towns are engaged, respectful, smart and inquisitive.

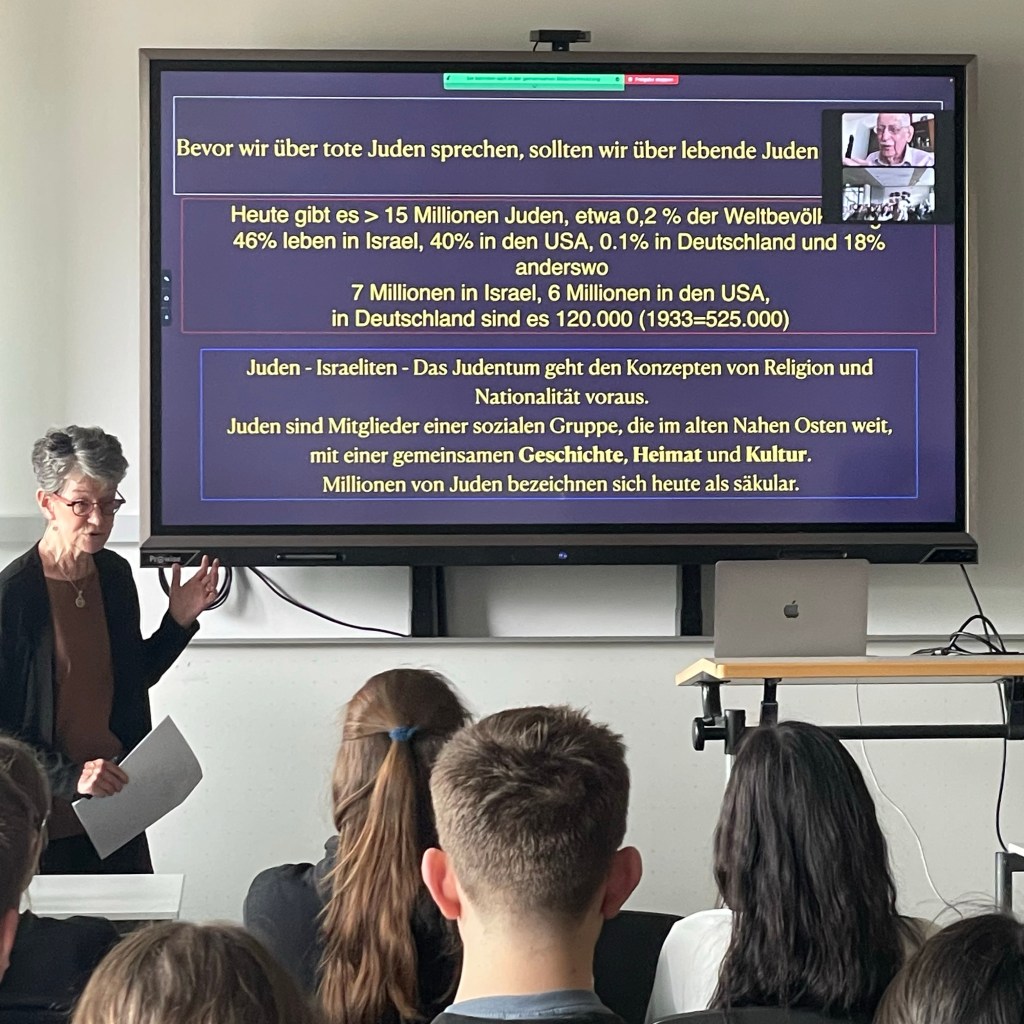

About 120 students in these towns heard my father via Zoom and me in person speak about the Jews who once lived here and my family’s experience during the Nazi era. Teachers, principals and the heads of each school were grateful for our visit and presentations.

My father spoke about the 1935 Nuremberg laws. Jewish Germans lost their citizenship. Jewish workers lost their jobs. Non-Jews were told not to shop in Jewish stores. Dad was forced out of the public school and had to commute via tram to a Jewish school in nearby Furth. Former friends called him “Jewish pig” and spat on him. Older kids dumped him into a box that held sand used on slippery streets; my dad cried for help until someone lifted the heavy lid. Neighbors marched and sang, “When Jewish blood spurts from the knife, all will be better.” My patriotic German grandfather was arrested and beaten by German officials simply because he happened to be Jewish.

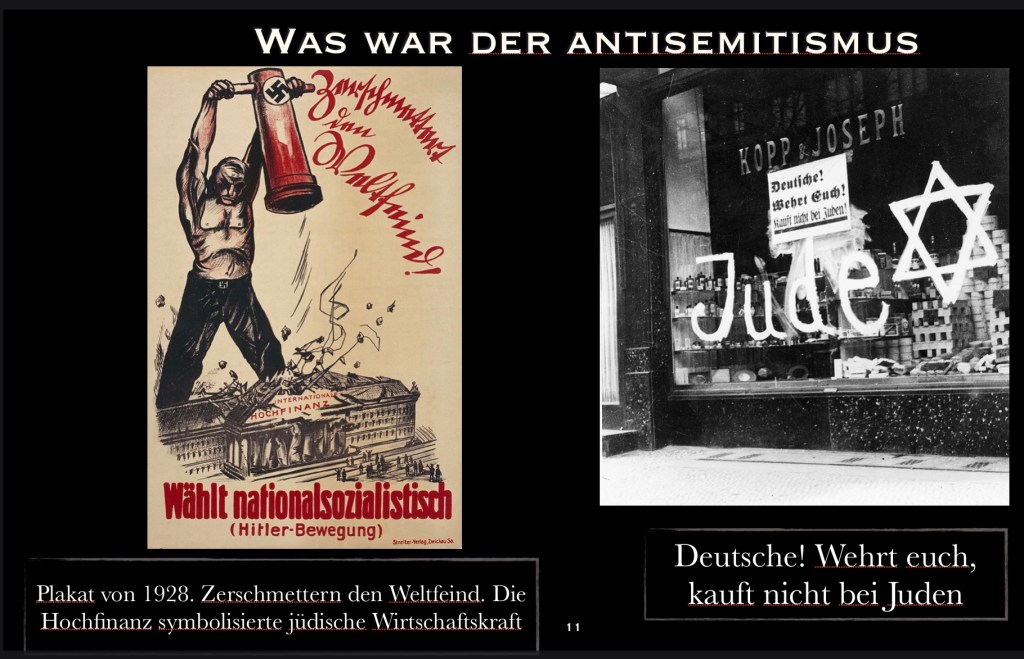

Nazi propaganda When it was almost too late, my father’s family escaped Germany to safety in New York City. The Freunds who survived dispersed around the globe.

I spoke about my family’s history before and after WW2. I cited the Brain Drain that hurt Germany and benefited the USA. I talked of the Jews from Germany who joined the U.S. Army and whose interrogation of captured German soldiers hastened Germany’s defeat in WW2.

Our description of our family’s deep German roots, persecution and exile left some of the students in tears.

The students wanted to know what life in America was like for my father. They asked whether I ever would consider moving to Germany.

These presentations were made possible by our friends Achim and Ronja.

Achim has been studying the Jews of Kleinwallstadt (the last of whom left the town in 1938) for 35 years, since doing a research paper in high school. Thanks to Achim’s research, we met our Freund cousin Chris for the first time ever.

Ronja coordinates programs for the local schools and also completed a project on the Jews who once lived in the area.

The Josef-Anton-Rohe school in Kleinwallstadt with Achim, me, Ronja and Chris.

Cousin Chris, Ronja, me and Achim

Kleinwallstadt students

A lovely thank-you card and gift from Kleinwallstadt In both towns, we spoke about the Jews alive today, what Judaism is, and that Hitler didn’t invent antisemitism. Our slides and verbal presentations were in German.

Students in Elsenfeld On the wall in the Elsenfeld classroom is this sign with words from the Talmud in Hebrew and German: Save one life and you save the entire world.

We Americans can learn from these students who are confronting their country’s history. Our country’s treatment of (among others) today’s First Nations tribes and the descendants of enslaved Americans should command as much of our attention.

After the sessions, Achim treated us to refreshments.

Rolf, Franziska, Renate, Achim, Jeffrey, me, Ronja, cousin Chris and Alexander Then he walked with us through Kleinwallstadt to visit houses and businesses, a war memorial and a former school, monuments and a former synagogue—traces of Jewish Germans who for centuries were part of this community until hatred and laws and violence made them disappear.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #23 – Born in the USA – May 15, 2023

DNA analysis confirmed what I already knew: I am 100% German Jewish. On this date some years ago, my German-born parents happily welcomed me into the world.

My wonderful, supportive husband (who would rather we were almost anywhere else in the world) gave me the silver necklace I’m wearing today, filled with a 1920 buffalo nickel to remind me of my American heritage. I love it.

Close-up. On the coin’s obverse is a portrait based on Oglala Lakota Chief Iron Tail and Cheyenne Chief Two Moons. This trip is hard. Every day we have spoken about the Holocaust, met people who are working on memorials or are otherwise focused on preserving Jewish history, or spoke to high school students. There is no escape, even on my birthday.

We have travelled far to remember my family. I felt the need to find the graves of my great-great-grandmother and her daughter because I may not return. In the wet, weedy grass, some of it chest-high, I found their graves and recited Kaddish (the Jewish memorial prayer), with tears in my eyes. Every day, something gets me choked up in Germany.

As we were leaving the cemetery, we met Barbara, who is on a bike trip. We stopped to chat. Barbara said that her parents and grandparents were silent on the Holocaust, saying that they had known nothing. During the unrest of 1968, teenage Barbara and her friends rebelled and demanded the truth from their elders.

Barbara and me. Barbara feels strongly that Germans must own their past and must continue to take responsibility for the murder of their Jewish and other fellow citizens and neighbors. She supports a Germany that protects human rights for all. I stood at my great-grandparents’ doorstep to pay tribute to them.

Selma and Willy Grünstein’s shoe shop is now a pizzeria. Next, we met Georg, Gaby and Iris for a tour of Miltenberg’s Jewish past. All three work to preserve the history of Jewish Germans. Georg and Gaby organized the installation of 44 Stolpersteine (stumbling stones) in Miltenberg and have helped families understand the history of this town. It is unfortunate that former synagogues here have no signs indicating their history. Outlines left by mezuzot can be seen on some houses.

This is not an easy topic to digest, particularly on one’s birthday.

Nancy, Iris, Gaby and Georg. My birthday lunch was at the Riesen Hotel. No one knows exactly how old it is, but official documents date it to 1411.

The star is not the Star of David, but a sign that the establishment is allowed to brew beer.

Iris and I toasted another year of life! The same star is on the coat of arms at our hotel, founded in 1881. It’s a relative newcomer to the neighborhood.

Jeffrey and I walked along the lovely Main River at the end of the day.

We had a few moments between birthday calls to relax.

My loving and supportive husband of 43 years. I am grateful to have been born in the USA, and thankful that my grandparents got my parents and themselves out of Nazi Germany before it was too late.

I never have met an immigrant who didn’t miss the sights, sounds and smells of home. For me, America is home. At the Passover Seder, Jews say “next year in Jerusalem”; today I say, next year in New York City with my family for my birthday.

Tomorrow it’s off to the Freund family hometown of Kleinwallstadt and nearby Elsenfeld for two more presentations to high school students.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #22 – Walking in the Wald – May 14, 2023

Picturesque Miltenberg sits an hour’s drive from Frankfurt along the Main River, where Viking tour boats stop.

In Miltenberg, our friend Ulrike Faust greeted us warmly. Our families have known each for about 100 years, as my two grandmothers (sisters) and their siblings grew up here and attended the local school. My great-grandmother, a smart businesswoman, ran a shoe store solo after her husband died. My Miltenberg based Grünstein family survived WWII, moving from Miltenberg to Haifa or New York before it was too late.

Ulrike and me at the start of our day. Our strongest family connection is through my Aunt Charlotte. In 1932, at age 9, she saved Ulrike’s 5 year old aunt from drowning in the Main River. The story made the local press. (Click here for details in last summer’s Essay #10.) After WWII, our families reconnected and now we, the next generation, are friends too.

We walked into the gorgeous Wald (woods), a favorite pastime of my parents when they visited their permissive grandma.

The Wald On these trips, I try to imagine the lives of my forebears. My Miltenberg family lived with their non-Jewish neighbors in peace for a long time. Then came WWII, when neighbors murdered neighbors, or looked the other way.

Tikkun Olam (Hebrew for “repair of the world”), means coming to terms with the past and building toward a peaceful future, often one person at a time. The Germans I have met on this trip acknowledge past evils and want to insure they never happen again.

My grandfather Adolf Steinberger said that one can’t live in a country where one has no rights. The Germans whom I call friends understand this. They promote human rights and denounce demagogues.

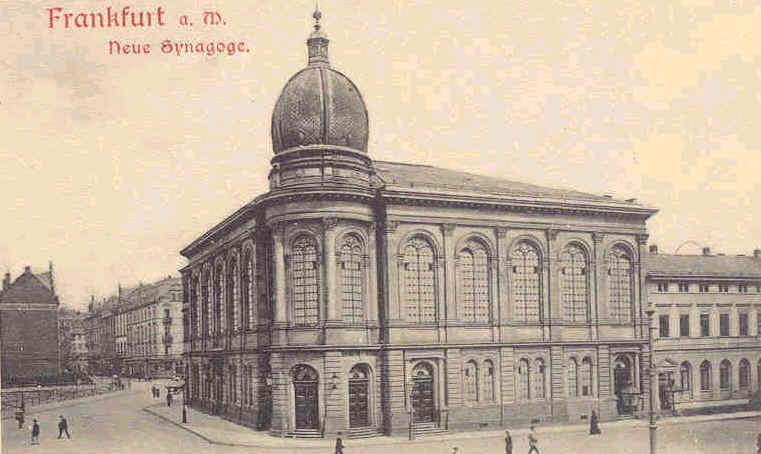

Beautiful Miltenberg. Jews lived here for centuries. The first synagogue was built in 1290. The last Miltenberg Jews were deported and murdered in 1942. Though we had not planned to go into the old Jewish cemetery, we decided to jump over the fence. My great-great-grandmother and my great-grandfather (among others in my family) are buried here in Miltenberg.

The old Jewish cemetery dates from the 15th century.

The grass is waist high.

My kinswoman Lina Grünstein’s grave We stopped at the Miltenberg museum. Several Jewish families were highlighted, their humanity shown in the face of their fellow Germans’ inhumanity. The museum displays a few Jewish ritual objects, some of them broken. I was left wondering what exiled or murdered family owned them and how they came to the museum.

Mira Marx was taken from Miltenberg and murdered. “Everyone in Miltenberg knew her. Mira was not a ‘Jew’, she was a person. Mira was just Mira. She was a petite older woman, who was polite and friendly to everyone, but otherwise lived modestly herself.” I found it interesting that the whole town was invited to the dedication of the new synagogue in 1904. My family must have attended the ceremony. They were gone when their neighbors burned it to the ground in 1938.

Celebration ticket for the dedication of the synagogue in Miltenberg on the 26th, 27th and 28th of August 1904.

Miltenberg synagogue, dedicated 1904, destroyed 1938. Ulrike prepared a fabulous lunch! She introduced us to some of her family. We had a wide ranging conversation and quickly realized that we share views on the importance of human rights.

Annette, Jeffrey, me, Ulrike and Toni

Gesine, Jeffrey, me, Ulrike and Toni

I need to add, that this morning, before we left Frankfurt, we stopped to peer into the Struwwelpeter Museum. Anyone with German parents will recognize these dreadful stories. If you have no idea what this is, look HERE.

Who knew there was a Struwwelpeter museum! We had another day to remember, a day of friendship (Freundschaft) for which we are grateful. But always in Germany, we feel the sadness of loss; the removal from Germany of our family, our people, our culture.

“Jewish Population in Miltenberg”: since August 13, 1942, it has been zero. No Jews live in Miltenberg today.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #21 – Frankfurt am Main – May 13, 2023

It’s just an hour’s drive to Frankfurt from my mother’s hometown. The Frankfurt cathedral is our new neighbor.

Jeffrey drives carefully on Autobahns without speed limits. It’s a relief to arrive.

Our spiffy rented BMW has been great. Friends Anna and David met us for a personal walking tour. Our first stop was the memorial to the nearly 12,000 Jews who were deported from Frankfurt and murdered.

This the grove of trees stands in place one of Frankfurt’s synagogues on what was the Jewish street or Judengasse.

My words fail to convey the impact of 12,000 small cubes, each with a name of a person, the date of birth and date and place of murder (if known) on a wall that stretches around a city block. Here I felt deep sorrow.

I am standing in the middle of the block on one side of the memorial. We came to pay tribute to my family, Marcus and Theresa Strauss born Steinberger, who lived in a beautiful house in Alsfeld (Grünbergerstraße 20) shown in my last post; and to Therese and Heinrich Freund who lived in Fulda until the Jewish school was destroyed and they were forced out. All moved from their small towns to Frankfurt around 1939 for the big-city anonymity that gave Jews some short term cover, though in the end, no better outcome.

The whole wall is many times this long. The beautiful synagogue was burned to the ground on Kristallnacht.

The synagogue in Frankfurt. In the same location is an old Jewish cemetery. The earliest provable burial was nearly eight hundred years ago. Jews lived in what has become Germany since Roman times.

The grass could use a cutting. Anna and I posed in front of Karl the Great, better known as Charlemagne, born in 748 (no digit missing), who went on to be Kaiser.

In 771, Charlemagne became king of the Franks, a Germanic tribe living in parts of present-day Germany, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. A skilled military strategist, he spent much of his reign waging war to accomplish his goals. In 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor.

Tour boats line the Main River. I’d never seen anything quite like this human food truck.

Fresh wurst? We didn’t taste. Lunch was out of the tourist area where locals dine. The food was good, the weather cooperated and the company of our friends was wonderful.

Lunch with Ana, David, Jeffrey and me.

Anna and David chose my first German beer of this trip.

Charming old town Frankfurt was rebuilt after WWII to look old. The original was bombed flat.

We stopped at an indoor market with flowers and food of all kinds. This store stood out for its German-ness. And then is was time to say goodbye. We have been busy from morning until night; today, we took it a bit slower. Wishing everyone a good Saturday.

Anna is expert at selfies. To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #20 – Archive Dive & Museum Memorabilia – May 12, 2023

In Alsfeld, we were fortunate to meet with good people who work to preserve Jewish history. Among them are Joachim and Claudia, who took two days off work just for us. They have been interested in Jewish history for decades and have been helping me for years.

Joachim arranged for us to meet Vice Mayor Berthold Runner, as the mayor (Bürgermeister) was in Washington, D.C. In addition to Kaffe and Kuchen and a warm welcome, we were presented with a gift!

Left to right: Claudia, Joachim, Jeffrey, Nancy, Vice Mayor Berthold and Sascha.

We toured the Rathaus (City Hall). Note the detail of the door and lock. The Rathaus was built in 1536, 240 years before our Declaration of Independence. A metal strip was used as a standard to measure cloth in the town square.

Claudia and I show the measuring strip’s length. Last year, I saw my grandfather’s name (Adolf Steinberger) on a curious box in the local museum. This year, I asked to see it up close.

I’m pointing out my grandfather’s name to Joachim. Sascha Reif is an archivist with a PhD—and tools! He opened the glass case (not easy) and let me hold this Aliya box bearing my grandfather’s name. I couldn’t suppress my tears.

To hold a religious object that my grandfather held in synagogue 100 years ago was surreal. Sascha and I will continue to exchange details of my family’s history in Alsfeld. What was the box used for? It seems to be one of a kind, made of wood and paper, with seven holes. My mother told me years ago that this box was used to call up Jewish men (in those days, only men) for a public reading from Torah on the Sabbath. The first one came from the priestly class (Cohenim, descended from Aaron, written in Hebrew on the top right). The second was from the Levi’im class, descended from the tribe of Levi. Then came five men from the general public, the Israelim. My grandfather, synagogue president, was one of the Israelim. I’ve indicated his name in the red box below.

After holding this box, I needed some time to compose myself. We walked to the doorstep of my mother’s house, 28 Alicestraße, now occupied by three families.

The house faced the yellow railroad station, topped with a clock.

My mother learned to tell time from the station clock. Nearby was the home of my great aunt and uncle at Grünbergerstraße 30. They were murdered. Their gorgeous house, across the street from the site of my grandfather’s clothing factory (which burned in 2007), remains.

In front of the house are two stumbling stones, Stolpersteine, for Aunt Therese and Uncle Markus. Murdered. I could hardly breathe.

These plaques have victims’ details, including the site of their murder. The pen is for scale. We met with Norbert Hansen, Alsfeld’s chief archivist. He greeted us warmly and was ready for us, showing us my grandfather’s 1922 and 1929 construction permit applications for his factory building. The applications’ calculations and details would spin your head.

I wish I had known my grandfather Adolf.

The 1922 factory building plan. We walked to the site where the beautiful synagogue stood. Only a plaque remains.

“Here stood the synagogue, inaugurated in 1905, destroyed on 11/9/1938 by National Socialist terror. The sufferings of the Jewish people call for the defense of human rights, resistance to violence and the lawless persecution of dissenters.”

This model shows how the synagogue looked from where the plaque now stands. In the 1930s, Alsfeld lost its Jewish community with its culture and contribution to daily life. But for fascism, I might have lived here. Gott sei Dank, thank God, for those who work to preserve that community’s history.

There is another building I wanted to see.

My great-grandparents, Isaak and Johanna Steinberger, were born around 1846. They lived at Hersfelderstraße12, about 2 minutes’ walk from our hotel, on the right side of this house.

My mother (born when her grandmother was 74) said her grandmother was strict but loving. Isaak and Johanna are buried in Alsfeld.

In Alsfeld, our long time family friends, the Dittmars, always invite us for coffee and cake. On my right is a family friend who introduced us to the schools in Alsfeld, greasing the skids for my presentations to students.

Kaffe and Kuchen Tomorrow we head south to Frankfurt, where we hope to have some time to decompress. We shall see.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #19 – Alsfeld – May 11, 2023

Alsfeld High School We started the day in Alsfeld, my mother’s hometown and home to my Steinberger family for at least 300 years.

We were greeted by Sarah Schaefer, a smart and engaging English teacher at the Max-Eyth School. Sarah made this visit possible! Sarah and I have been talking for months on Zoom. The key, we thought, was to prepare a presentation that would bring to life the experiences of Jews who lived in town and were forced to emigrate or were murdered.

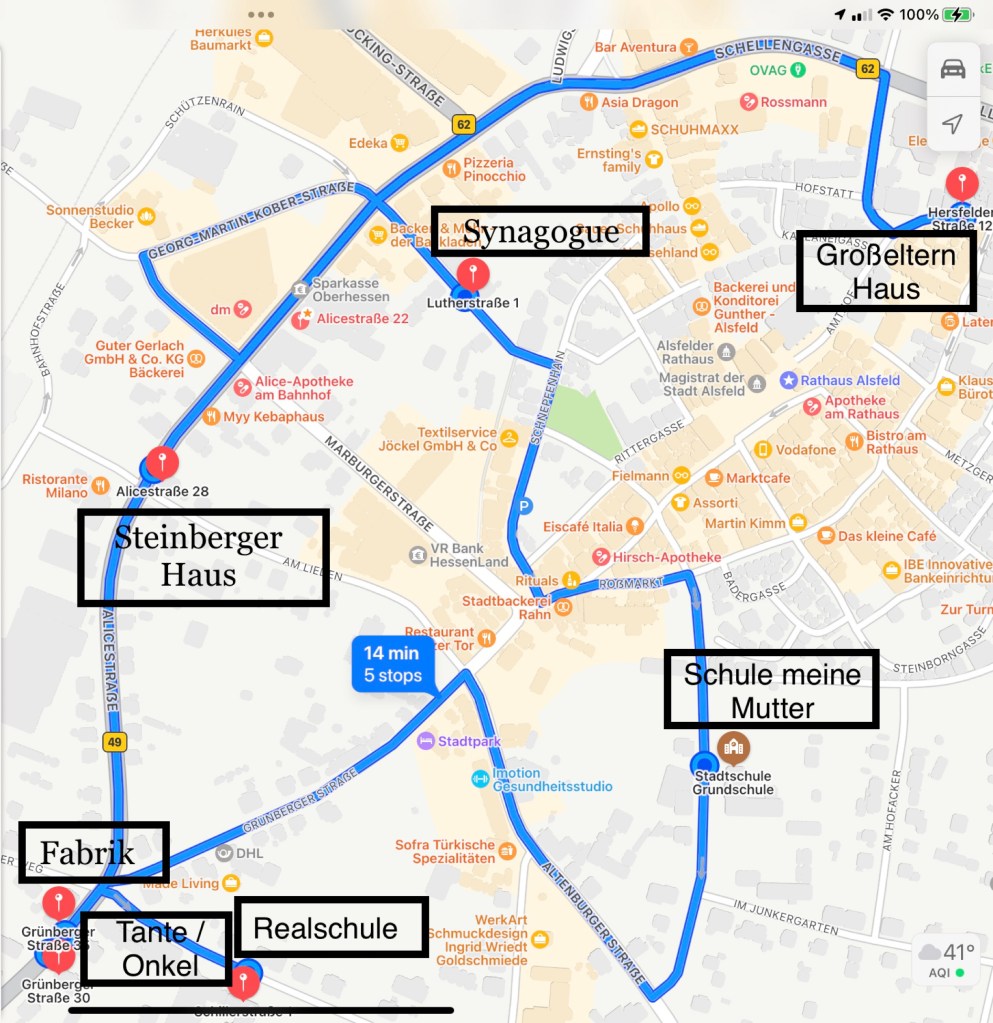

Alsfeld is the little blue dot on the map. It’s a 45 minute drive from our stop in Fulda yesterday. Alsfeld is 62 miles north of Frankfurt, with a population 16,000. On this map, I showed the students the house where my family lived, the public school they attended and the synagogue where they prayed and where my grandfather was president. My family felt very German, yet my grandparents were smart enough to uproot their family, 8 months after Hitler took power, and move to Haifa.

My Steinberger family house, the Fabrik (factory my grandfather owned), the Schule (school my mother attended), the house where my Tante and Onkel (great aunt and great uncle) lived, the synagogue and house of my GroßEltern (grandparents). I showed the students lots of photos, including where my mother was born, where the synagogue stood and where my grandfather’s factory with 130 workers stood. Of course they knew all the locations. Alsfeld is a small town. One student actually lives in my mother’s old house, though he was not in attendance.

My mother’s house was across from the (yellow) train station. Several students shared their thoughts and feelings. Ferdinand stayed to speak with with us and to be interviewed by the local museum, which filmed one of the classes. Ferdinand thinks that we should learn from the past. Some students apologized on behalf of their great-grandparents. One thanked me for sharing my story while others nodded agreement; she said my personal story and the setting in her own town made real the pain that went with emigration and the trauma that was passed on through the generations. Some mentioned that their ancestors never spoke about the Nazi times, or had said they were indifferent when the Jews disappeared. Others said they had great-grandparents who were in the SS.

Ferdinand stayed well beyond the class time.

I spoke in German to about 75 students in three classes over 4 or 5 hours. Some of the students went to the same school as my mother. History teacher Andreas Scheumann and his class joined us after a brief lunch. I somehow didn’t get a photo of him. His students were fully engaged and asked numerous questions.

I shared my complicated feelings about Germany. On the one hand, my home in suburban New Jersey was typically German, with German food and customs. When I came to Germany the first time, it felt much like home. On the other hand, many family members were murdered. It’s hard to reconcile except to believe in helping innocent young Germans to understand this history so it never repeats.

It will take time for the students and their teachers to process what happened to today. Millions of murders and millions of refugees are hard to fathom. The story of one family from your neighborhood is easier to grasp.

The teachers will speak with the students and share their reactions.

After class, we drove to Speier Haus in nearby Angenrod.

In 1942, Gestapo criminals forced the last 8 of Angenrod’s 247 Jews onto a truck to be deported and murdered. In protest, while the criminals searched his house, Leopold Speier got off the truck and cut down his family’s pear tree. In 2021, German students planted this pear tree as “a new sign of life in diversity and unity.”

Some of the house interior was left untouched after Gestapo vandalism and the deterioration of abandonment.

A staircase records anti-Jewish obscenities from 1920 until the present: before, during, and after the Nazi era in Germany. Dedicated volunteers have made Speier Haus into a center to educate students about the local Jews who were murdered or forced into exile; and to teach the students that Jews are not fossils, that We Are Still Here, even if not living in Alsfeld and Angenrod. I gave Speier Haus some Jewish ritual objects and information to help further their goals.

Then Jeffrey and I took our German friends to dinner. They gave me some sweet local treats and a book about Alsfeld published on the town’s 800th anniversary in 2022.

My brain is fried. It was a good day. A memorable day. An emotional day. And a German-immersion day.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #18 – Fulda, Germany – May 10, 2023

Delta Sky Club, JFK Airport, New York City The first step on any trans-Atlantic journey is the trip to the airport (this time via the M57 bus and E-train) and the chaos of checking in. Only when I reach the Delta Sky club do my nerves begin to settle.

We landed in Frankfurt around 8am and drove directly to Fulda, where I was scheduled to speak to students at 2pm. Fulda is a town of 70,000, founded in 744 (no typo) around an abbey. Before WW2, there were about 1,000 Jews out of 30,000 inhabitants. Today there are 300 Jews, almost all from Eastern Europe.

We took the short route to Fulda. We are two jet lagged travelers. I have a link to Fulda. My distant cousin Heinrich Freund (born in the Freund family hometown of Kleinwallstadt) and his wife Therese Freund (born Stern) resided in Fulda for more than 20 years. The couple lived in the basement of the Jewish school, though his job is unknown.

Henrich and Therese moved to Frankfurt in 1939 because the synagogue was destroyed on Kristallnacht and the school building was “sold”. Both were deported from Frankfurt and murdered by the Nazis; he in Theresienstadt (age 74) and she in Treblinka (age 75). The town of Fulda remembers them and other Jews who lived here. There also are memorial plaques for this couple in Frankfurt, which we plan to see next week.

We were greeted in Fulda by Anja Listmann, a quiet powerhouse, the Commissioner for Jewish Life in Fulda.

Me and Anja In researching my family, I came across the memorial stone in Fulda for Heinrich Freund.

Memorial stone for Heinrich Freund The City of Fulda’s website lists Anja as the person responsible. One phone call later, I had a ton of information and an invitation to speak to her students.

Awesome Anja is an example of what one person can accomplish. In her teens, Anja listened to her grandmother speak about the Jews who once were their neighbors. Disturbed and inspired, Anja (who’d had no inkling of this) dedicated her life to recovering Fulda’s Jewish past. She teaches students about the Holocaust and human rights, unearthed the local mikva, and has convinced the city to rebuild the synagogue in some form. She unearths documents in the city archives to create family trees and family histories.

This was the Jewish school and home of my cousins Heinrich and Therese Freund. Anja has about 20 students per year who volunteer to research the Jewish history of Fulda. They visit Auschwitz with her and do other projects. There is no school credit. The students are people of conscience and character.

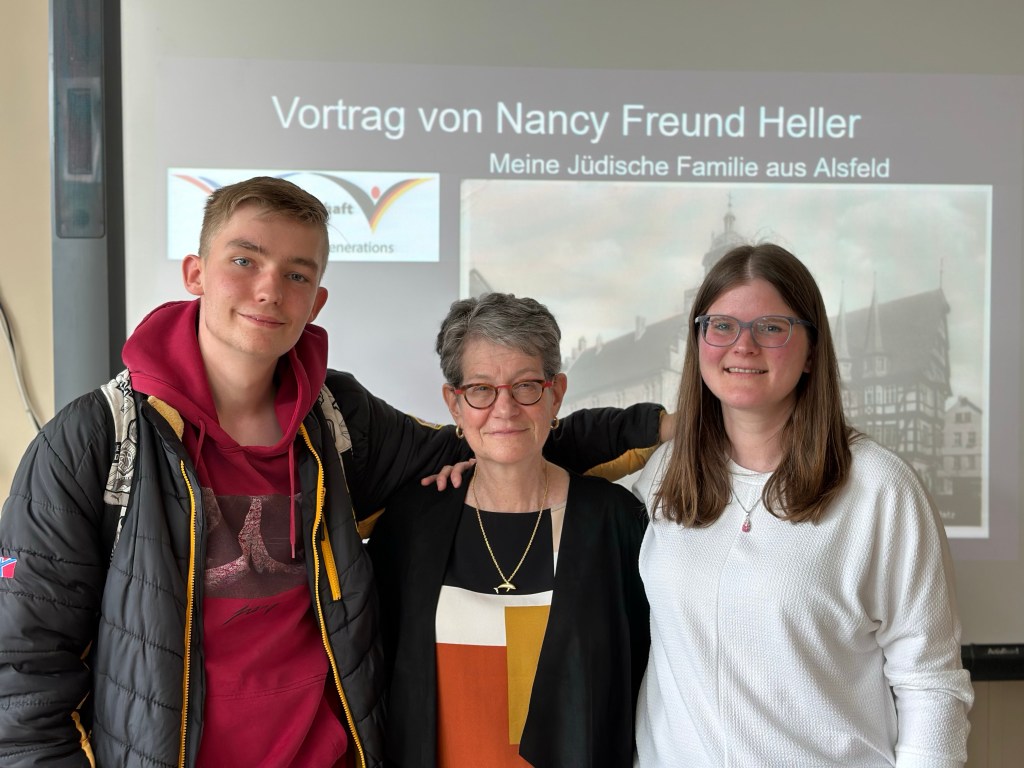

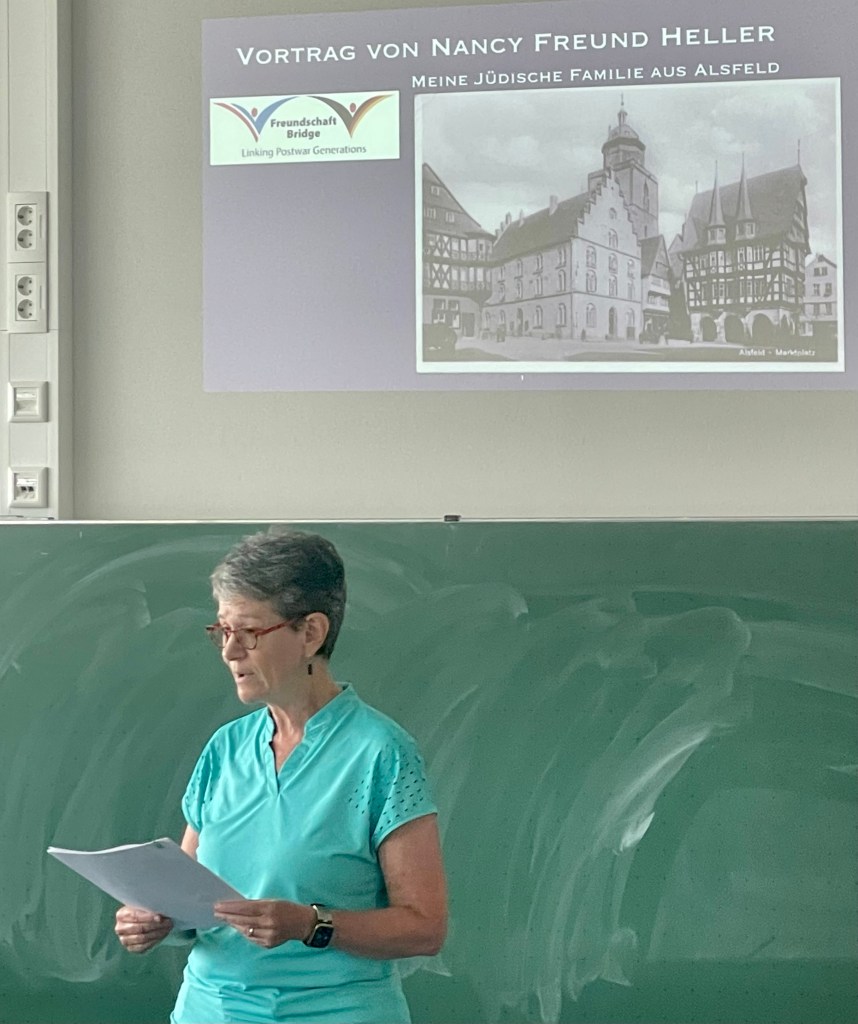

After a short introduction I spoke about my Bavarian Freund family and Hessian Steinberger family that came from the nearby town of Alsfeld, just 40 minutes up the road. The students were engaged. After my talk, they made comments and asked questions.

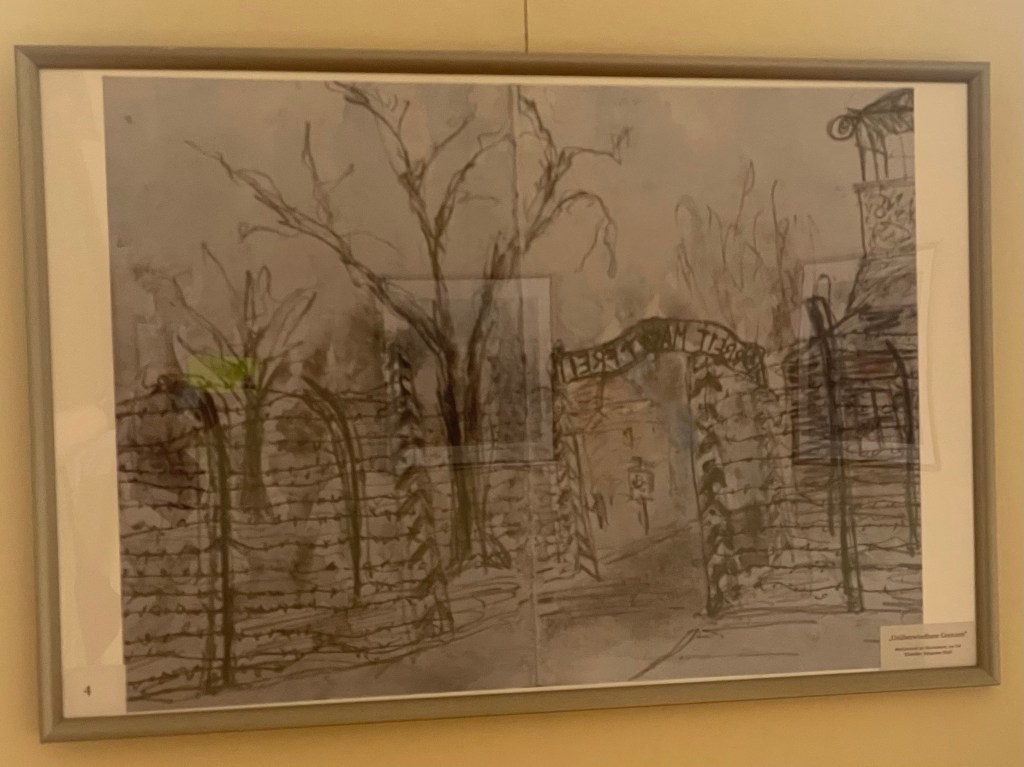

Speaking German to students in Fulda The students created an exhibition in City Hall after their visit to Auschwitz. The pictures and poems are worthy of any museum.

This year the students have partnered with a high school in Petach Tikvah (near Tel Aviv) to learn from each other. Next year, the Fulda students will visit Israel; the following year the Israelis will come to Fulda.

The first known Jewish presence in Fulda was about 1300 years ago. Records from 1423 mention a synagogue. The Jewish population was recorded at 1,137 in 1925 and 1,038 in 1933.

In the 20th century, Fulda’s orthodox Jewish community thrived—until their non-Jewish neighbors betrayed them.

Fulda Synagogue in 1927

The synagogue’s interior

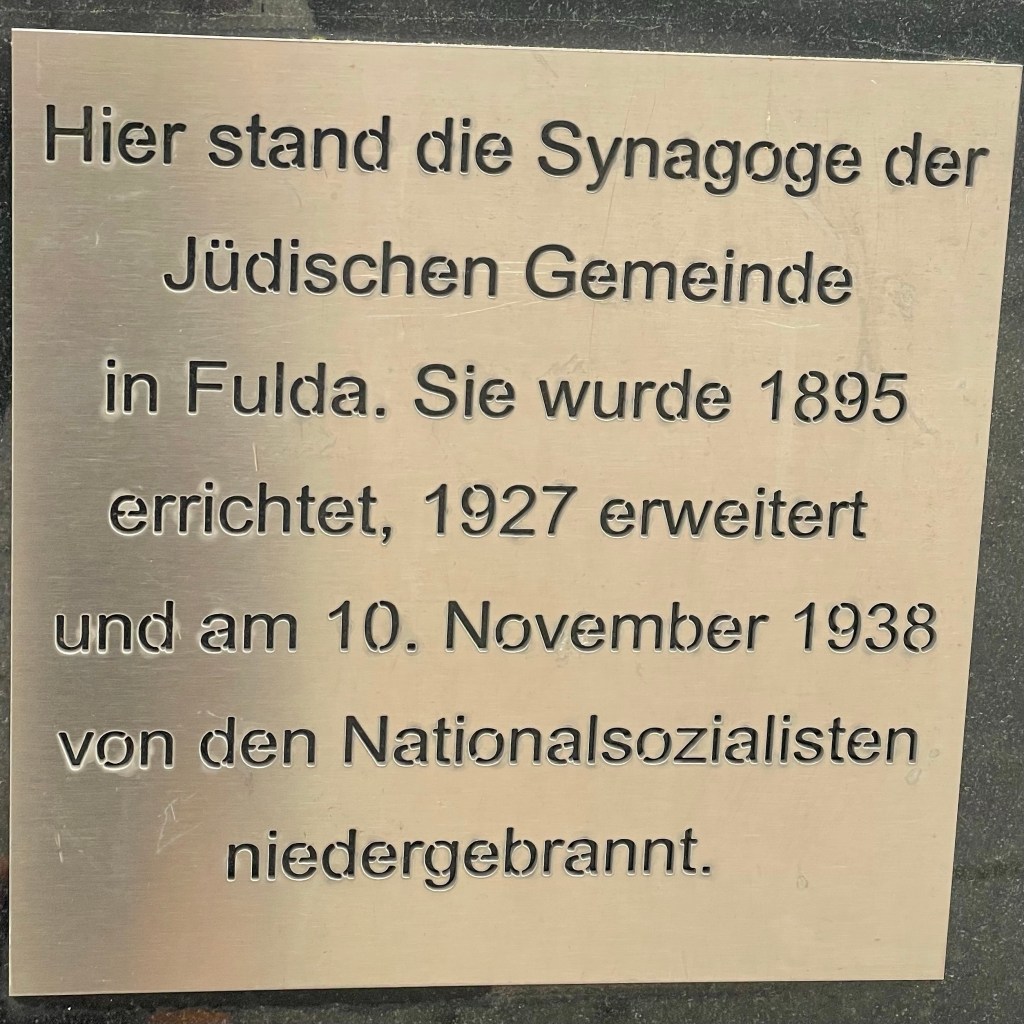

“The synagogue of the Jewish Community in Fulda was located here. It was built in 1895, expanded in 1927 and on 10 November 1938 burned down by the National Socialists.” Thanks to Anja, the Jewish community’s long presence will be felt once again.

Her work is a paradigm of tikkun olam, the Jewish concept of repair of our broken world.

To read prior essays please click HERE.

-

Essay #17 – Yom HaShoah – April 17, 2023

Tonight (after sundown) begins Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, and we remember the lives of those forced to flee and those murdered in Shoah.

Thanks to good luck and some smart grandparents, ich bin hier, I am here. I’ve been interested in family history for decades, grilling my parents on their past and more recently digging deeply into genealogy research and trying to make sense of it all. There is little sense to be made, but there is much to be learned.

My family on both my mother and father’s side, lived in Germany for hundreds (perhaps thousands) of years. I’ve traced us back to the 16 and 1700’s. One of my Freund forebears was a Schutzjude, or privileged Jew, with the right to own land in a small town called Kleinwallstadt or small walled town. Next month, my dad via Zoom and I in person, will speak to high school students in this town about the Nazi period and my family history in this town. My great grandfather fought in the Franco-Prussian war and a monument in the town bears his name along with the other town fighters. This great-grandfather ran a dry goods store, was a wealthy man and a leader of the Jewish community. I will tell the students that under other circumstances, I might have been their neighbor.

Liebmann Freund fought for Germany Not all my Freund forebears made it out of Nazi Germany. On this trip, a Stolperstein, or stumbling stone will be placed for my blind great aunt Karoline in Nürnberg, my father’s birthplace. Next year, 2024, my great uncle Max and great aunt Bella will have stumbling stones, also in Nürnberg. I will be there.

Little 8 year old Anneliese and her parents Friedrich and Irene Sänger were all murdered in Piaski. Max and Bella Freund of Nuremberg died in Riga. Karoline’s daughter, (Irene) son-in-law (Friedrich) and granddaughter (Anneliese) were all murdered and the city of Munich will place memorials next month on the sides of buildings, thinking that the Jews were stepped on enough and it’s better to have memorials on eye level. As part of these memorials, I agreed to honor the siblings of the blind aunt’s son-in-law. I spent almost a year researching their past and writing their biographies. I will deliver their eulogies in German, which I’ve been studying for the last six years. Of course I never knew any of them. My dad, now 96, remembers walking his blind aunt across the street in Nürnberg.

My dad’s father, Hugo Freund, was rounded up in Nurnberg, a hot bed of the Nazi party even before Hitler took power. Hugo thought things would blow over until he and the other Jewish men were badly beaten and forced to run around a track until exhaustion. That was enough. With permission from the American consulate in Stuttgart in 1937 (a miracle unto itself), my 11 year old dad and his family managed to get a visa from a distant cousin, money for tickets from a rich brother-in-law, exit permits and a new life.

My mother’s family lived in a small, pretty old town, Alsfeld, with 16,000 inhabitants an hour north of Frankfurt. Jews lived there for maybe 500 years. Next month, I will speak to 100 students in my mother’s home town, kids in the same school that my mother and aunt attended. It will be surreal to show them a town map with my mother’s house, the family business, the synagogue. All of these kids will know the locations. I will show them photos of the business my grandfather ran with the 100 employees standing outside. Some of the employees were their great-grandparents. I’ve asked the teachers to show the photo to the kids so they can ask their parents if they recognize their family. This will be up close and personal and uncomfortable for all of us.

Alsfeld, German the picturesque hometown of my mother. I will show these Alsfeld students Stolperstein of my great aunt Therese and her husband Markus that lie under their noses in town in front of the house where they lived, where it’s clear that they were murdered by the Nazi’s. I will tell them that a Nazi thug came to shoot my grandfather in 1933, around Purim. My grandfather’s workers warned him to get out of town, and my grandfather – Adolf Steinberger- was smart enough to know that without civil liberties one cannot live. In August 1933, taking one last look at the town, as their father advised, my 13 year old mother and her family moved in the dead of night, to Haifa.

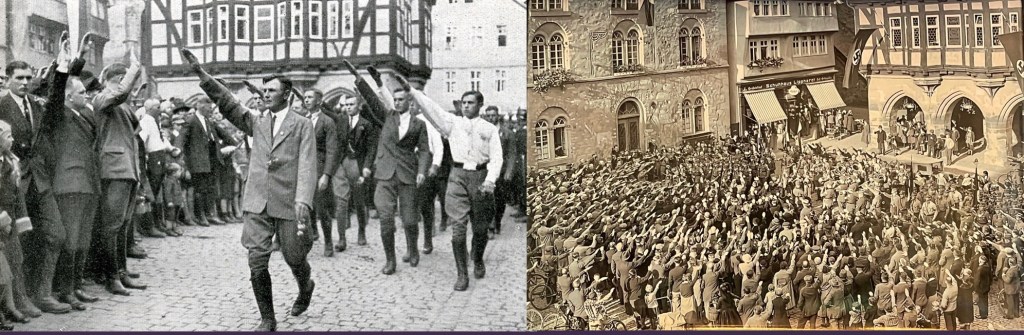

My great aunt Therese and her husband Markus lived in this beautiful house. They were deported and died in Lotz. In both my mother and father’s towns, I will show them photos of local townspeople (their families) chanting antisemitic slogans that my parents had to hear. Wenn das Judenblut vom Messer spritzt, dann geht’s noch mal so gut. “When Jewish blood spurts from the knife, things will be good again.” It will likely send shivers down their spines and scared my parents half to death. It’s hard to imagine the scene of hundreds of local townspeople marching, saluting and chanting slogans against their neighbors.

Propaganda from 1928 encouraging people to vote for the Nazi party and smash the international high financiers (read Jews).

In 1932 the local residents were marching and saluting in my mother’s hometown chanting antisemitic slogans. And from all this horror, I hope to help all of us learn from the past, to vote for freedom. I hope that they come away feeling that we all have a responsibility to fight for civil liberties and keep despots from ruling our lives. Remembering is not enough. We have to do something.

I have mixed feeling about Germany, where a part of me feels so at home. Germany has a long history of Jew hatred and robbed many of their lives. Yet this new generation, like myself, was born after the war. Growing up, the shadows of the Holocaust were ever present. From these ashes, I believe that we, Germans and Jews together, can and should work do our part for Tikkun Olam, the repair of the world.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

-

Essay #16 – Awestruck – February 2023

What is awe?

From devoting.com: “Awe induces a sense of wonder/amazement so overwhelming that we are a bit afraid”—like standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon. Nature can be humbling, and makes us feel small.

History humbles too.

I feel a sense of awe from my genealogy work, meeting new relatives, finding new documents, and talking to Germans who are preserving Jewish history.

I am moved by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s song (which originated when Nash was with the Hollies), Teach Your Children Well, with its call for parents and children to understand that each generation goes through its own “hell” (growing pains/life issues) and to respect and learn from each other. (Click on blue highlighted letters to open links.)

Grand Canyon, North Rim. Awesome. Last week, in the Lincoln Center Performing Arts research library, I paged through The Handbook of Biographies of the Jews in City and Region of Aschaffenburg. Having parted with my coat and purse, as required to prevent theft of this Columbia University book, I read in comfort and safety about my dead relatives in a town now devoid of Jews. I felt awe—tempered with dread.

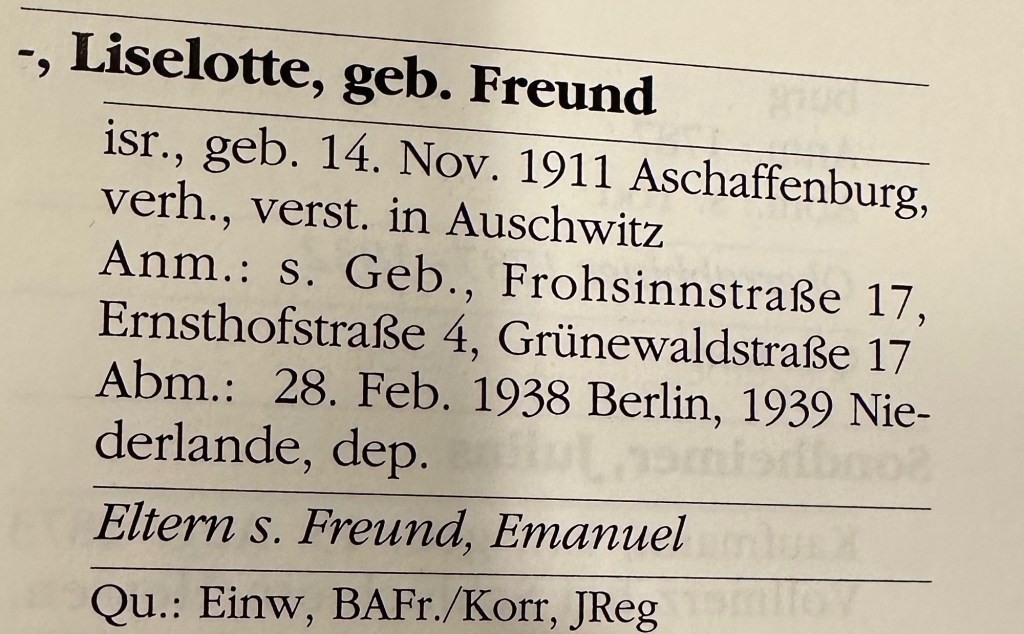

From the book: Liselotte Freund, born in 1911, lived in Aschaffenburg. She was murdered at Auschwitz. When I started genealogy research, asking my parents hundreds of questions and creating photo-journal books and family trees, it never occurred to me that this project would grow into something much larger. I never imagined that I would teach German teenagers about their past from the experiences of my parents and from my view as a first generation American. I did not guess that I would work with local governments in Germany to establish family memorials.

I struggle with the idea that I am the right storyteller. As Clint Smith wrote in a recent article in The Atlantic magazine, Monuments to the Unthinkable, “Germans are still trying to figure out how to tell the story of what their country did, and simultaneously trying to figure out who should tell it.”

My German tutor reinforced the fact that from the ashes of WW2 arose a new Germany, just as the United States arose from the Revolutionary War. My tutor thinks that I have an open way of connecting with today’s Germans, as we share our trauma from the past and find a path to a better future. I hope she is right.

The generation that survived Nazi Germany is disappearing before the German people have fully faced up to their history.

WW2 is as ancient for today’s German high school students as the Spanish-American War was for me. I am grateful to the student and adult volunteers in small towns across Germany who engage with that history and its impact on Jewish Germans. I look forward to meeting them this summer.

Once I too was in high school. (Not shown: my purple paisley bellbottoms.) See the Star of David pendant? I was not shy about my Jewish heritage. This photo of my father (at right, age 9), with his sister and his father, was taken in Germany in 1935. That year the German government enacted the Nuremberg Laws.

Even before the Nuremberg Laws, the Nazis barred Jews from their professions, their businesses were boycotted and they were subjected to harassment and violence. The new laws stripped Jewish Germans of their citizenship, barred marriage between Jews and other Germans, and barred Jews from flying the German flag. My family had been German since the 1600s. With the stroke of a pen in 1935, they became stateless, hated Jews who happened to be in Germany.

In 1933, Jewish businessman Oskar Danker and his Christian girlfriend were forced to carry these signs. The words rhyme in German. Hers: “I am the biggest pig here and engage only with Jews!” His: “As a Jewish boy I take only German girls to my room.” In 1933, a local Nazi shot into my mother’s home in Alsfeld; thankfully no one was hurt.

If the United States treated me like this, I would pack a bag and run. Yet hindsight is 20/20. My grandfather, like many Jewish Germans, thought the madness would blow over; surely their neighbors would vote the Nazis out.

I find it hard to believe that the Holocaust ended barely a decade before I was born.

In May, I will meet in Fulda (pop. 70,000) with German 9th and 10th grade students who have volunteered for the Fulda-Auschwitz project. Project coordinator Anja Listmann, whom I met while I was researching my dead relatives, invited me to speak with her students.

From Fulda, I will drive to my mother’s hometown of Alsfeld (pop. 17,000). After the local Alsfelder Allgemeine newspaper published an article entitled We Are Still Here (send me a message if you want the English translation) about my visit last summer, I subscribed to the weekly edition.

Recently a different Alsfelder Allgemeine article caught my eye. It was about local high school students passing advanced English language exams. I reached out to the school. Plans are underway to visit teacher Sarah Schaefer and her class. The students are studying Naziism. I look forward to a good discussion in English and German.

From Alsfeld I will drive to Bavaria and the Freund family hometown of Kleinwallstadt (pop. 6,000) where Achim Albert has arranged for my father (from New Jersey via Zoom) and I (in person) to speak with students in the area.

Returning to my ancestral towns on this mission has special meaning. In The Atlantic article, Clint Smith wrote, “no stone [memorial] in the ground can make up for life. No museum can bring back millions of people. . . . Yet we must try to honor those lives, and to account for this history, as best we can.”

I will do the best I can.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

______________________

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.