I’m home and thinking about our trip to Germany.

Many smart, kind, generous people made this trip possible and special.

Already, I miss the coffee and my new friends.

On prior trips to Germany, I couldn’t sleep. I feared that Hitler would jump out of the closet in my hotel room or that I would be arrested on the street. In those days, former German Nazis were alive and well.

Today, the youngest Hitler voter would be 110 years old. A Nazi soldier aged 18 in 1945 would be 95 now. My fear of the old Nazis is gone.

Many thoughts whirl in my head. This trip involved visits to my family’s hometowns and to historic sites, and talking about the present and the past with today’s Germans. This was not a cemetery tour. We did not say Kaddish for people I never knew or met. “Been there, done that.”

This tour engaged me with Germans born after WWII. We put aside who was responsible for the war. None of us in the post-war generation was responsible for anything.

Like me, these Germans were raised by parents who had suffered. My parents’ trauma came from being frightened and uprooted, from being strangers in strange lands. The Germans’ parents were scarred by invasions, bombing, hunger, years of military service, years in prison camps; some screamed in their sleep.

Our parents’ traumas great and small influenced our childhood development. We shared stories and the effects the war era had on us, the second generation. We lived with parents who acted out their pain, or refused to talk about their experiences, or searched for their lost childhoods. Sometimes this made us anxious and scared. Sometimes we pass our anxieties on to our own children.

My German contemporaries and I became friends. Our friendship has eased my mind. Our exchanges were meaningful and cathartic for all of us. My hope is that we can heal some of one another’s pain.

As I traveled from place to place, I couldn’t escape the fact that the Jewish people rooted in Germany for centuries, have vanished. Larger cities have a few Jews and synagogues, but most of those Jews are from the former Soviet bloc. There are a few Israeli transplants. The Jews who spoke and ate and joked and kept house and lived like my parents and their parents, are gone. They left Germany or were murdered.

It makes sense that the German Jews made new lives elsewhere for themselves and their descendants. But many Germans today miss the diversity that my family and others brought. Some of my new friends told me that they’re sad that people like us don’t live in town. They said that with Jewish neighbors, their communities would be more vibrant and interesting. We would have been friends.

Yet although most of Germany is as Hitler wished—Judenrein, free of Jews—my people triumphed in the end. My grandparents’ Jewish granddaughter stood atop the annihilated dictator’s Nuremberg platform. I towered over him!

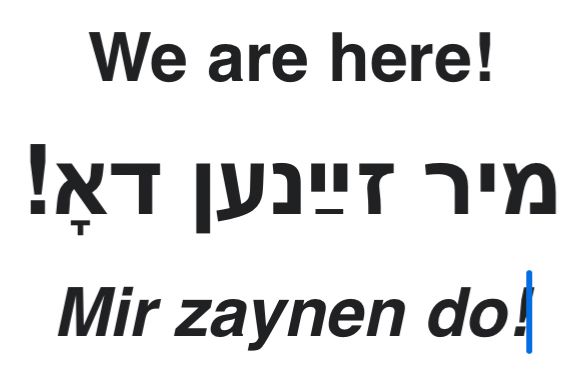

As my husband says in Yiddish, the language of his grandparents, mir zaynen do.

I thank everyone who made my trip so meaningful. There are too many to name. A few of the many who stand out:

I thank my German tutor of four years, Daniela. Her teaching let me connect with (and impress) German speakers. She worked with me to translate old family letters to better understand what my parents and grandparents lived through.

I thank my therapist for helping me handle the complex emotions stirred up by this trip.

I thank my children and their spouses, and my sister and my dad for supporting me along the way. That my dad, now almost 96, traveled with me vicariously was wonderful. He answered questions and spoke to me daily, adding color and context to our family’s journey to America.

And most of all, I’m beyond grateful to my supportive husband, my beschert, my soulmate, Jeffrey, a Litvak for whom Germany is a disconcerting and alien land. He drove me over 1,000 miles and put up with hearing hours and hours of German every day. This was an emotionally difficult trip for him. Married for 42 years, best friends for 43, I’m lucky to have him in my life.

At the end of a trip, I’m always happy to return to familiar sights, sounds and smells: to my own house, family, food and coffee. It’s hard to imagine never returning home, as my parents and so many immigrants experienced. The fear of being forced to live where you don’t speak the language is hard to grasp.

Thank you for reading my blog, commenting and sending me messages of support. It means a lot to me.

I hope that this journey inspires us all to have more empathy for those fleeing tyranny, and to welcome newcomers as they try to make a new life in a place they never wanted to call home.

I wish you all a safe journey.

—Nancy

To read prior essays, click HERE.

Leave a reply to Jennifer Kawar Cancel reply