Today we are in Aschaffenburg with our dear friend Iris. Iris volunteers with a local organization to digitize the history of Jewish families (complete with family trees, birth certificates and other documents). She even enters phone book information. A former English teacher, Iris is the main contact for English speakers who visit and she is a great tour guide. We met Iris last summer though we have been corresponding for years. How I wish we were neighbors.

Iris has opened her heart and her house to us. We demolished this delicious homemade strawberry cake with cream (Schlag in German) at the end of the day.

I get ahead of myself. Let’s go back to the start of our day now that you have seen the end.

Iris took us to a farmers’ market to shop for the dinner she will cook for us tomorrow night. Tomorrow is Ascension Day, a national holiday in Germany, and everything will be closed.

It was Freund/Heller laundry day, which is not an official German holiday.

Aschaffenburg is an important stop for me because many Freunds moved from little Kleinwallstadt (population 6,000), where yesterday we spoke to students, to busy Aschaffenburg (pop. 45,000 when my family lived here, 30,000 after WW2, 70,000 today).

Where did they live? What did they leave behind?

Great Uncle Emanuel Freund was a university educated engineer with a very successful family business called “The Brothers Freund” that provided electricity to towns and homes in the area. The business also sold cars and bicycles. Emmanuel (born 1882) lived in a big beautiful house with his wife Betty Fromm and three daughters.

Emanuel and most of his family emigrated to Chicago at the eleventh hour, in 1939, where his engineering knowledge lit up houses and businesses. There is something poetic in this story: German Jews exiled and American cities light up. Despite frantic family efforts, the eldest daughter (Liselotte Siddy Solinger, born Freund) could not escape; their fellow Germans murdered her.

We walked the path Emanuel would have taken to work, all the while thinking of him and his family and the comfortable existence they had enjoyed before Hitler. Leaving their home was hard. I often wonder how I would have acted under these circumstances.

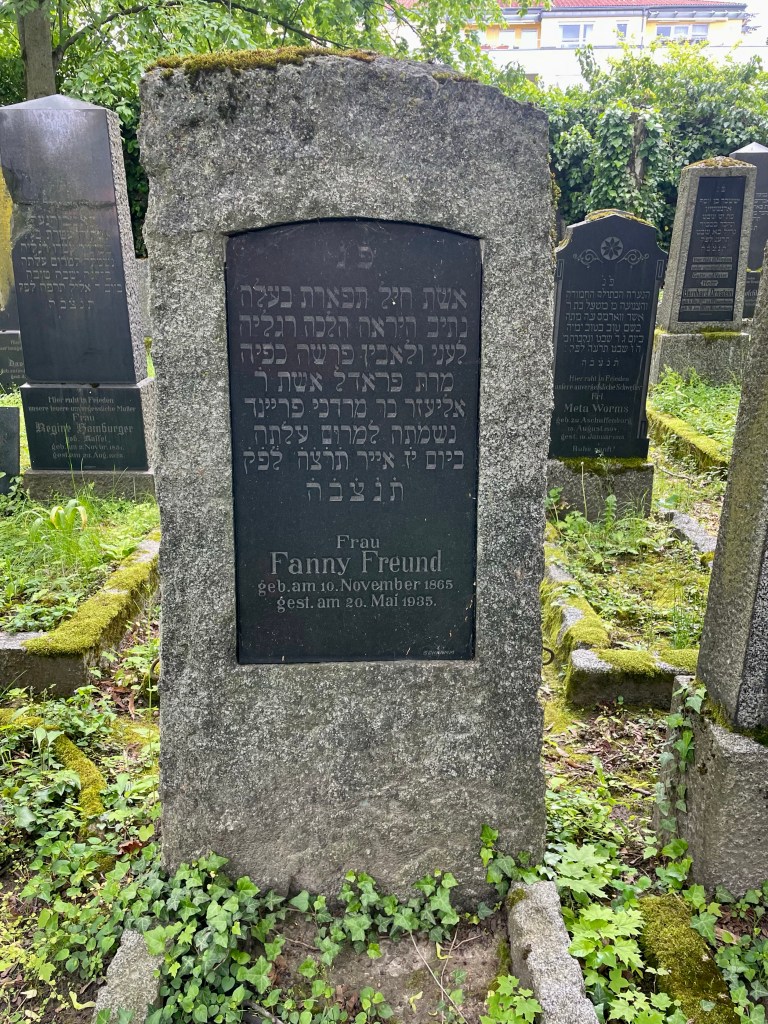

Though I have been to Aschaffenburg several times, I never had been to the Jewish cemetery in the city itself. Iris showed us family graves that we had never seen. Dad participated on FaceTime.

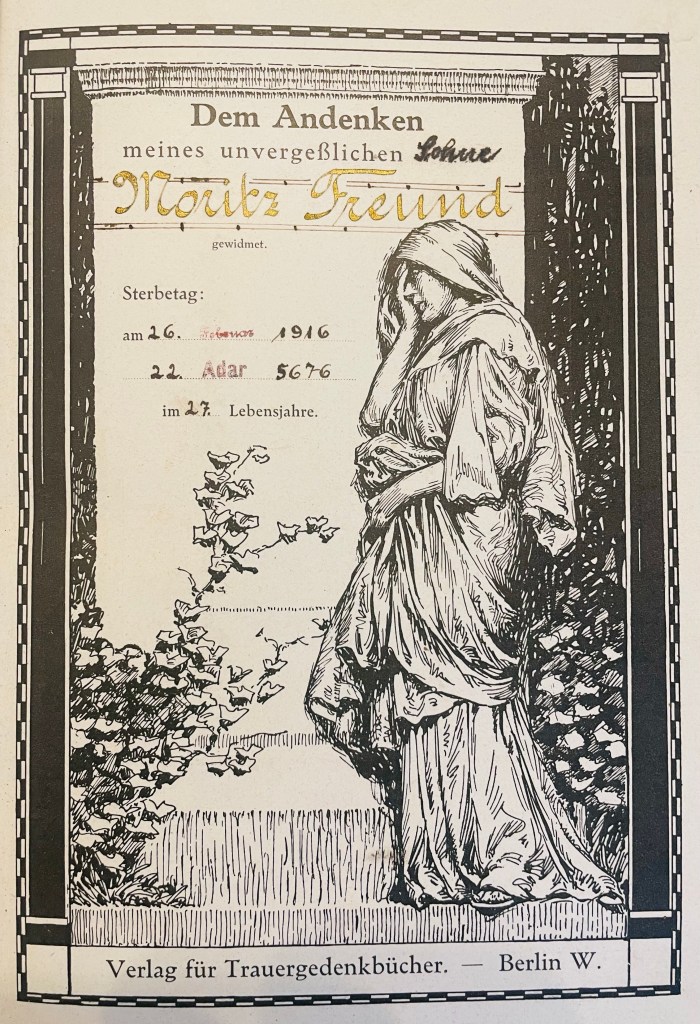

Emanuel was child number four of eleven children. My grandfather Hugo (kid #11) was his brother. Another brother, Moritz Freund (#9), died in France in 1916, fighting for his German Fatherland. Moritz’s parents were given a memorial book, shown below.

I stood at Moritz’s grave.

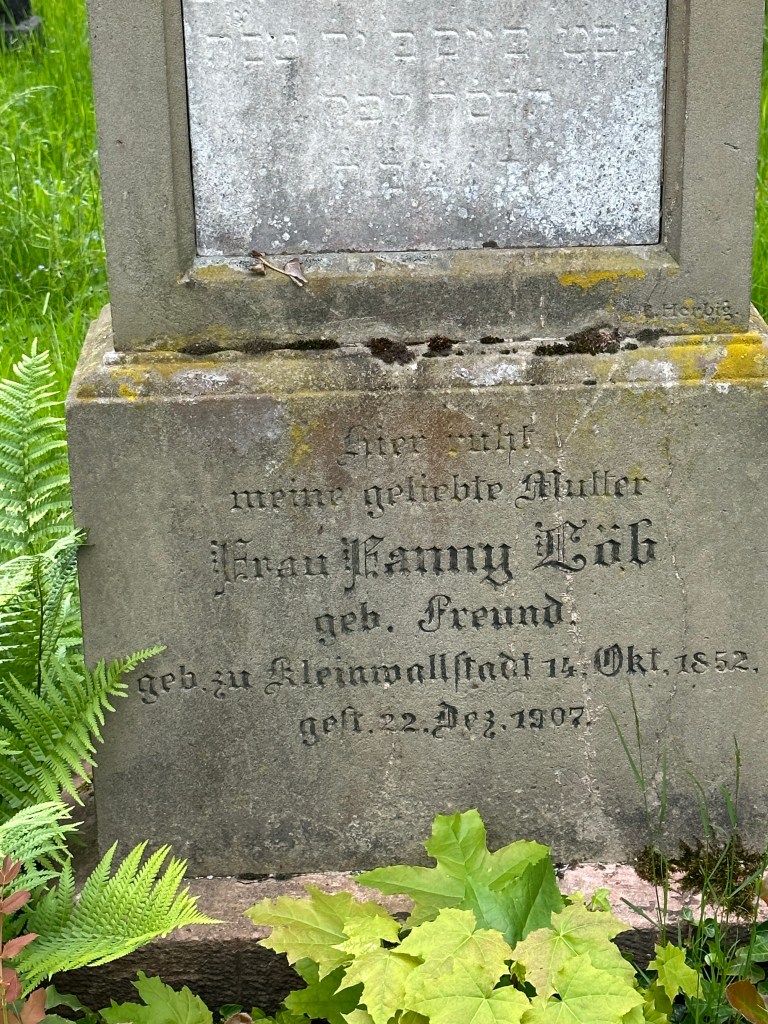

Other family members are buried in this cemetery, including Fanny (born Kochland) and Lippmann Freund. This couple had one daughter, Irene Freund.

What would my 19th Century Aschaffenburg family think of their American relative who came to photograph their gravesites and honor their lives.

In this same cemetery are graves of German soldiers who died in WWII. Some German soldiers were innocent victims of the Nazi regime. Not these men. They were in the SS.

Slave laborers from Eastern Europe who survived WWII are buried in this cemetery, near a memorial to WWI Russian prisoners of war.

No one on earth actually remembers any of these people. Time makes the horror seem distant. But it’s still horror.

Remembering the past is useless unless we learn from it, and apply that learning.

I hear the voice of my mother’s father Adolf Steinberger in 1933: “In a country where you have no rights, you cannot live.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt said on January 6, 1941, “Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere.”

What I saw today evoked my family’s suffering during and between the World Wars. I hope it inspires thoughts and actions, in me and in others, to help repair our broken world.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

Leave a reply to Nina Charnley Cancel reply