After returning from Germany in June, 2022, my father suggested that I turn my attention to having memorials placed for those who were murdered by the Nazis. Now in January 2023, I sit at my desk in New York City with a new mission.

To determine who in my family perished, I took a detailed look at my family tree, which now has 590 names. Since the German government decided that a memorial should be at the last residence that was “freely chosen” by a Jewish person, I need an exact address to give to the appropriate town or city. As part of my research, I have found family members previously unknown to me who share an interest in our history. This journey brings together a family that was scattered around the globe and seeks to understand what the hell happened, if any genocide can ever be understood.

In many ways we are among the more fortunate. Many in my family managed to get out of Germany before it was too late. Though such escapes gave the German Jews a greater survival rate than countries like Poland with many more Jews (more on that in another post), all of my relatives who did not leave Germany before WW2 began were murdered. Of those who fled, only one Freund relative, who had moved from Germany to Holland before the war, survived deportation to a concentration camp.

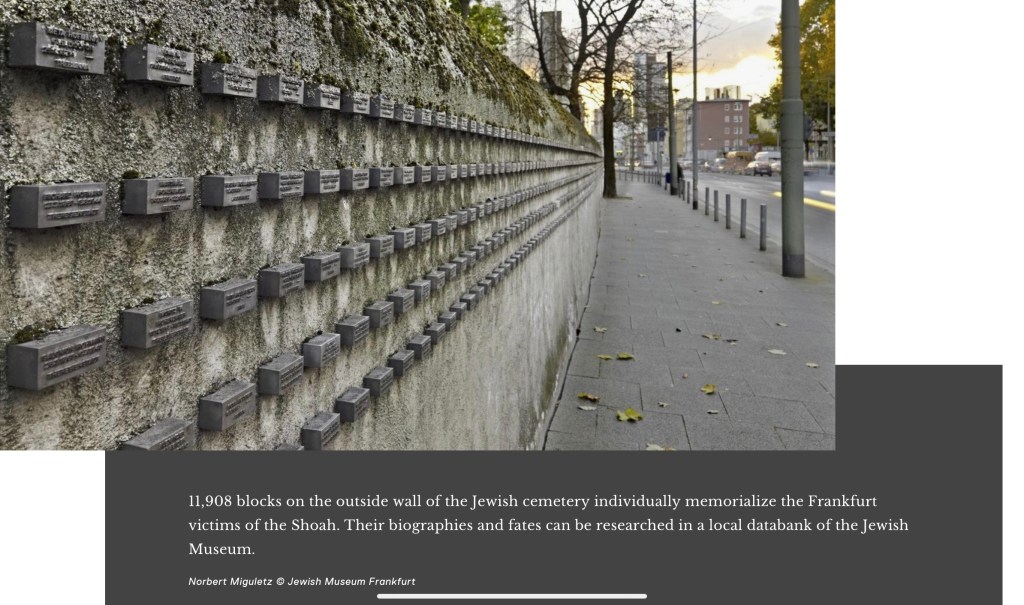

The victims of the Nazi regime are remembered in Germany and elsewhere with many types of memorials. In some cities, like Nürnberg, Alsfeld and Aschaffenburg, Stolpersteine or stumbling stones (brass plates) are set into the street in front of the house where the Jewish person lived. In Frankfurt, there are steel blocks with the names of nearly 12,000 Jews in one place! In Munich, memorials are placed on the side of buildings and columns outside the houses. In Fulda there are real stones outside the synagogue.

This is personal. Members of family either already have a memorial or will have a memorial in each of these cities mentioned in the coming years. I have been working with the cities of Nürnberg and Munich to remember my Freund family in May 2023 and in 2024. I plan to see all the memorials that are in place, most of which I have not visited because I did not know about them.

I never met my mother’s Aunt Therese Strauss née Steinberger or her husband Markus Strauss. They lived around the corner from my mom in Alsfeld. While my grandfather Adolf Steinberger moved to Haifa with his family in 1933 (my mother was just 13), Aunt Theresa stayed too long, trusting in Germany, declining opportunities to go to Cuba and South Africa.

Therese and Markus moved to Frankfurt in 1939 as Jews in small towns like Alsfeld felt the Jew-hatred. In a big city they could be more anonymous. No matter. They were deported to the ghetto in Łódź, then Poland’s second largest city, in October 1941.

Before the war, the city of Łódź had 230,000 Jews. Jews were 31% of the city’s population. By comparison, Germany as a whole had 500,000 Jews in 1933; nearly two thirds of them had fled by the time the war began in 1939. My great aunt and great uncle and Jewish deportees from elsewhere were forced into the Łódź ghetto. It had no water or electricity. The average person was allocated about 1,000 calories per day. Death came from starvation, disease, exposure, shooting, and forced labor. Therese and Markus perished there. Their sons, pictured below, got out of Germany before the war, one to South Africa and one to England.

The City of Frankfurt has erected a wall bearing steel blocks with the names of nearly 12,000 Jews, including my great aunt Therese and great uncle Markus and other Freund family members. My husband and I will visit in May. It is hard to imagine just how long is this concrete memorial.

Irene Freund, I wish I could have met you. In other circumstances, we would have met at family events because your father and my grandfather (cousins) were born in the small town of Kleinwallstadt, with a population of 5,700 today.

You were an independent, unmarried woman who had a career! You worked in Aschaffenburg as an office assistant and private secretary.

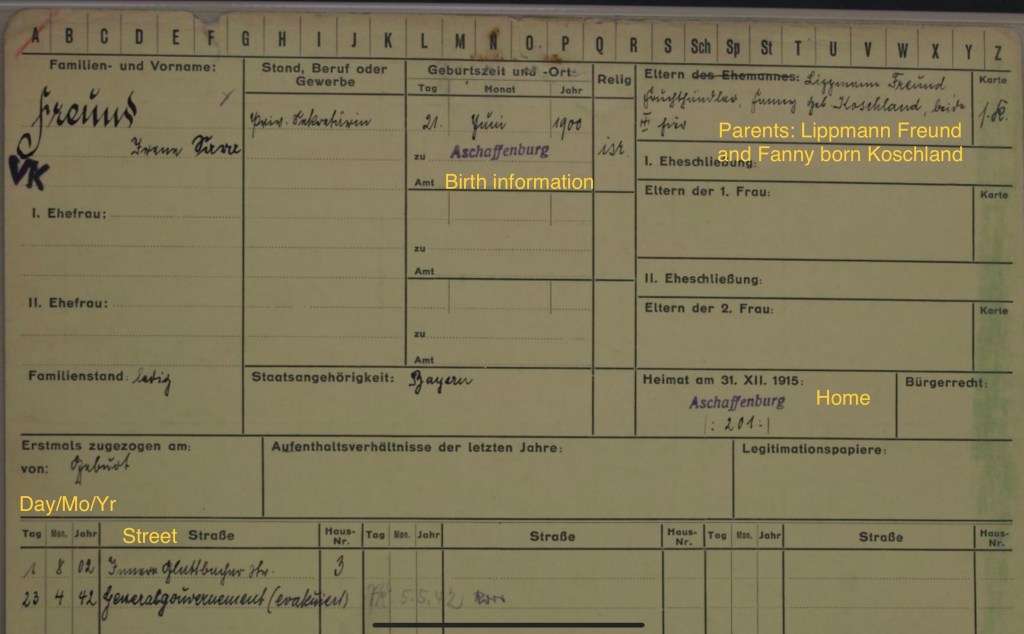

You were born on June 21, 1900 in Aschaffenburg, Germany. Your father, Lippmann Freund, worked as a fruit dealer who married Fanny, née Koschland.

On April 23, 1942, you were taken to Würzburg. Two days later, you were deported to Krasniczyn, Poland. You were murdered there or in another camp in the Lublin area in the same year. A stumbling block in Aschaffenburg commemorates you. You were just 42 years old.

You may know that the Germans long have kept detailed records of birth, death and every change of residence. But Nazi era records aren’t always easily available today. Not everything has been digitized. And sometimes local officials want to keep skeletons in the closet.

In the last six years, I have been studying German, which has helped me read the old documents that are scattered across the Internet. Below is an example from the City of Aschaffenburg with Irene Freund’s details.

In future posts, I will write about Freund family members who are just getting to know each other. I also will explain how I am working with officials in Munich and Nürnberg and will be speaking to students in Fulda, Kleinwallstadt and maybe other towns, on my upcoming trip.

In the meantime, you can read about Stolpersteine and watch a video about them here.

Leave a comment