Jeffrey here.

With Nancy.

In Germany.

“Not my country, man!”

Nancy’s parents and grandparents thought they were German—until the hate and violence of their German neighbors forced them to flee. My grandparents, who escaped the Russian Empire 30 years earlier, had no such illusion of belonging.

Still, Nancy and I are not so different. As in Nancy’s family, all my relatives who didn’t escape Europe by 1939 were murdered by the Germans and their allies. My kin died not in Germany, but in Belarus and Lithuania. All the military-age men in my family served in the U.S. Army in WW2, and thanks to the Germans, not all of them came home.

As I am the only member of our family without German roots, and I am Nancy’s only companion on this journey, Nancy asked me to share my point of view.

But first: ancient Heidelberg.

It’s a beautiful university town.

Jews lived here since at least the 1200s—except during periodic mass murders and expulsions. You know the drill.

And they live here again. A synagogue was built in 1994. It has about 400 members, almost all of whom are refugees from the former Soviet Union.

Jews from the east found a haven here. Jews with deep roots in Germany, like Nancy’s family, don’t live in Germany anymore.

Nancy’s family didn’t live in Heidelberg at all. So for us, being here was a bit of a rest. There are no family sites to see. No cemeteries with Freund/Steinberger/Grünstein ancestors. No inherited memories. To a greater extent than in our prior stops, we could just . . . be.

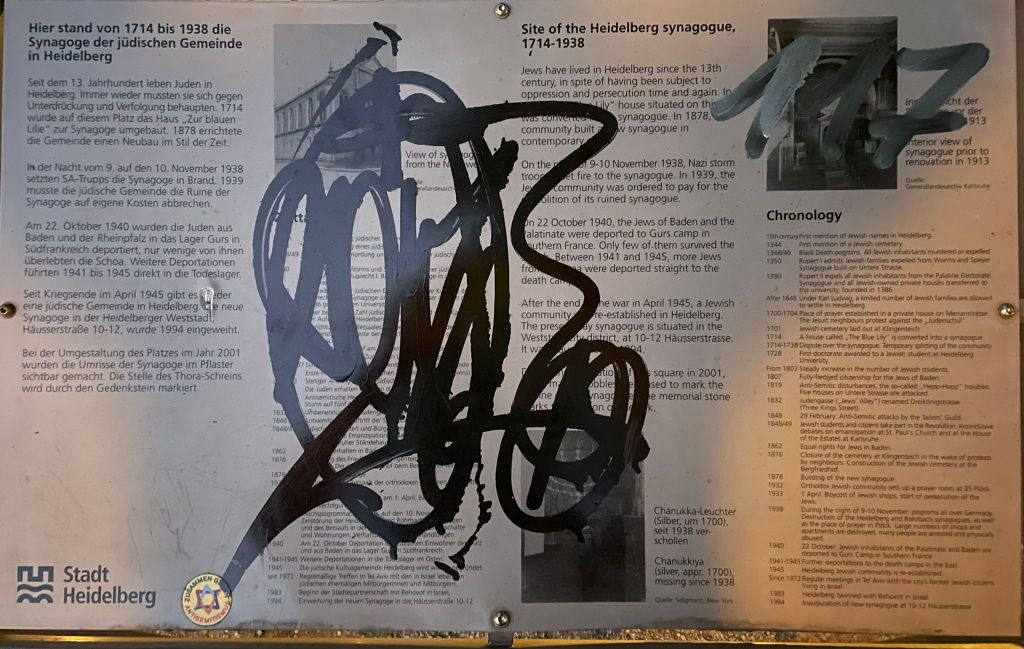

Still, Jews haunt this city. There are monuments.

Outside of Israel, anything Jewish is likely to be vandalized, of course.

Happily, there’s a silver lining to this vandalism of the site of the former Heidelberg synagogue.

Kind Melina is from the Alsfeld area, as was Nancy’s mother’s family. Melina isn’t obsessed with the past. But she knows it, has learned from it, and wants others to learn too.

Here are my early thoughts on our exploration of Nancy’s roots.

This trip was difficult for me. Every day I saw something that overwhelmed my emotions. Every day I visited sites where terrible things were done to Jews in Germany. Every day I felt a mixture of horror, sadness, anger—and gratitude to the Germans who by acknowledging their history, show their love for humanity and their regret for what their families and neighbors had done.

My experience isn’t far different from when I biked through the Deep South of the USA and saw monuments to black American victims of white lynch mobs.

Horror, sadness, anger—and gratitude. It’s a lot to process in America. And in Germany.

These emotions—plus the disconnect between the richness and beauty of this country, the kindness I see in the people I meet, and the horrors my people and others suffered at German hands—make Germany a hard place for me.

A hard place. Yet it’s a good place.

A few summers ago in a hot NYC subway car, a loud German tourist complained that the subway in Munich was much better than the NYC system. I silenced his obnoxious boasts by reminding him that his city’s facility was newer and better . . . because the USA bombed the old one. A new subway, and a new and more humane Germany, arose from the wreckage of WW2.

I think of this as I watch America’s recent slide toward fascism, never mind the deterioration of our infrastructure.

I ponder Thomas Jefferson’s assertion that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

I fear that blood might be shed in America by the hard-right cult of today’s pretend patriots who trample our Declaration of Independence and our Constitution. They imagine as tyrants the honorable American officials who obey the law.

And I wonder whether we will learn from today’s Germans. With our help, since WW2 they have largely if imperfectly faced up to their history, and built a society in some ways better than our own.

To read prior essays, click HERE.

Leave a reply to Jan Cancel reply